- Home

- Mike Carey

Vicious Circle Page 6

Vicious Circle Read online

Page 6

I dried my hands and went back out into the living room. Arthur was clashing his beak and shrugging his wings open and shuthis way of begging for more, but I was all out of goodies. I skirted around him, keeping my distance in case he decided to search me to make sure. Pen leaned in the doorway, arms folded, looking at me with some concern.

I dont know, I admitted. Something coming in on channel death. Or maybe nothing. You know how these things go.

Just by reading her face I could see her decide to change the subject. Grambas called, she said. Some men tried to deliver something at the office yesterday, but you werent there. Hes got it in the lockup behind the shop.

I grimaced. A pilgrimage out to Harlesden first thing on a Monday morning wasnt a thrilling prospect. On the other hand, that was meant to be my place of work, and since I owe Pen so much back rent that she could probably legally impound both my kidneys and sell them in Hong Kong, she feels fairly strongly that I should spend more time over there than I do.

But she sympathized with my raw mood, and as usual her sympathy took a concrete form. She cleared the tableby tipping all the newspapers, magazines, coasters, and unopened mail onto the floorand went to get her tarot deck.

Pen, I said, regretting that Id said anything, you know I dont hold with this stuff.

It never hurts to get a second opinion, she said.

From who? Whose opinion are we getting? Pieces of laminated cardboard dont know jack shit about whats going down in the world, Pen. Nobody ever tells them anything.

Its not the cards, Fix. Its you, and its me, and its the weltgeistthe world-spirit.

I winced and waved her quiet. The world-spirit. Right, because theres a consciousness in back of the universe and it loves all its children: we get daily evidence of that in terms of famine, plague, and flood. I dont buy the tarot for the same reason that I dont buy religion: the hopes and fears of ordinary people stick up out of the miracles like bones out of a spavined horse. My universe doesnt work like that, and the only spirits in it are the ones that are my stock in trade.

She gave me the cards to shuffle. I considered palming death and top-decking him while she wasnt looking, but she hates it when I do that so I played fair.

She dealt out a triskele spreadthree cards in a triangle, two more crossed in the center. Ordinarily shed have done a full ten-card spread, but she knows my limits so she was keeping it short and sweet.

She turned over the cover and the crossthe two cards in the middle. They were an inverted ace of wands and the hanged man. Pen blinked, clearly surprised and a little unsettled by the conjunction.

Thats really weird, she said.

Tall dark stranger? I hazarded.

Dont be stupid, Fix. Its just that those two cards, together like that . . . they mean exactly what you just said. Spiritual energynegative spiritual energyin a kind of suspension. Blocked. Frozen. Penned up.

I made no comment, but she didnt expect any. She turned over the root card at lower left: the page of swords, again inverted. A message, Pen interpreted. News. All the page cards mean something dawning, something being announced. I think . . . because its upside down . . . a problem that doesnt get solved, or that gets solved in the wrong way. Fix, if someone asks for your help with something, go in carefully. One step at a time.

The bud card at lower right was old death himself, which as we all know doesnt mean death at all. Pen started to make her speech about change and flux, and I made the wrap it up gesture that TV floor managers use. Its another bad combination, she said stubbornly, refusing to be bullied. The page of wands, and death. Forget what I said about being careful: youre going to trip up and fall on your face. But its only the bud, its not the flower.

The flower is the apex of the triangle. Pen turned it over, and we both looked at it. Justice. I never look at those scales without thinking of Hamlet. Use every man after his desert, and who should scape whipping? I dont want justice: I want to cop a plea.

Pen gave me a look, and I shook my headbut the querent doesnt get to have the last word, even if its only a gesture.

Things will balance out, she said. Actions will have the consequences they were always going to have. For better or worse.

Which? I asked. Better, or worse?

We wont know until it happens.

Christ, I hate these little bastards.

She gave up on spirituality and got the whisky out. On some things, at least, we still see eye to eye.

Three

HARLESDEN IS LIKE KILBURN WITHOUT THE SCENIC beautythe stamping ground of Jamaican gangsters with itchy trigger fingers, predatory minicab drivers whose cars are their offices, and a great nation of feral cats. Oh, and zombies: for some reason, those whove risen in the body seem to congregate in large numbers on the deserted streets of the soon-to-be-demolished Stonehouse Estate. Its a setting that shows them off to very good advantage.

My office is in Craven Park Road, next to the Grambas Kebab Houseor rather, my door is next to their door. The actual room where I conduct my meager and occasional business is on the first floor, directly over Grambass eternally bubbling deep fryers. On bad days I can see an intimation of hell in that image.

The sign over the door still says F. CASTOR ERADICATIONS, which these days is a pretty outrageous lie. Im not quite as free and easy as I used to be about toasting ghosts: I cant even remember the last time I did it, which on the whole is probably a good thing. But a man needs to have some stock in trade, and God didnt give me the shoulders or the temperament for hard labor. So Id finally taken a step that Id been considering for a while nowand it looked like today would be the day that made it official.

At ten on a rain-sodden May morning, Grambas hadnt even hefted the first doner yet. I knocked on his door and waited, wondering if he was awake. I got my answer when the window above and to the right of my head opened and a shiny bald head was thrust out of it. A pair of watery brown eyes stared down at me, taking their time to focus. To the waist, which mercifully was as far as I could see, Grambas was naked.

Fuck, he said thickly. It never stops. Come back at noon, Castor.

Throw me down the keys, I suggested. I only need to get that package out of the lockup.

He sighed heavily, nodded, and withdrew. The keys came flying out of the window a few moments later, and I almost went under the wheels of an ice cream van as I stepped backward to catch them. I went into the alley alongside the shop and let myself into the backyard through a door whose hinges were only held together by rust. The lockup, though, has a stout steel-reinforced door and three padlocks: Grambas knows his neighbors well, and though he forgives them their vices he doesnt see a need to finance them.

I took the padlocks off and left them hanging open in their eye-bolts. It comes naturally to me to assess the professional credentials of any locks I encounter: I learned lock-picking from a master, and though the world has moved on into realms of electronic key-matching and double-redundant combination codes, Im still okay with the bog-standard stuff that most people use. One of these three locks was generic, without even a manufacturers mark; the second was a venerable Squire, and the third was a sexy little beast from the Master Lock titanium series. Numbers one and two I could have handled without a key any day of the week, but for number three Id have needed a very long run-up indeed. Im not saying I couldnt have done it, but thered have had to be a damn good reason why I was trying.

Inside, the lockup was obsessively, immaculately clean. One wall was piled almost to the ceiling with neatly stacked boxes: on the other side, three chest freezers stood in a row like coffins. My package lay on the floor in the middle, with the single word CASTOR scrawled across it in thick black marker pen. It was five feet long, one foot broad, and only an inch or so thick. I picked it up, and borrowed

Grambass toolbox on my way out. Mine consists of three wrenches and a ball of string, and I last saw it in 1998. I snapped the padlocks back on again behind me and went back around to the street.

Id had the new sign made to the exact measurements of the old one, so this was a job that was just about within the scope of my meager DIY skills. I could even use the same screws, apart from one that had rusted through and therefore snapped off as I was getting it out. In spite of that minor setback, and the rain coming on heavier while I worked, within the space of about ten minutes F. CASTOR ERADICATIONS had become FELIX CASTOR SPIRITUAL SERVICES. I looked at it with a certain satisfaction. It was a circumlocution I was stealing from a dead man, but hey, hed died trying to kill me and hed thieved from me on occasion, too, so I wasnt going to beat myself up about that. The important thing was that I wasnt an offense to the Trades Description Act anymore. Now I just had to sit back and wait for the clients to start pouring in.

As to what spiritual services were, exactly, Id worry about that some other time. I was sure Id know them when I saw them.

When I took Grambass toolbox back round to the yard, he was coming out of the lockup carrying a gallon drum of frying oil in each hand. He stopped when he saw me, and put them down. I forgot to tell you, he said. You got a customer. Two, in fact.

I raised my eyebrows. That was a novelty these days. When? I demanded.

This morning. About seven oclock. They were standing in the rain out there when Maya came back from the wholesaler. She felt sorry for them. In fact she wouldnt stop feeling sorry for them, and she wouldnt shut up about it, so in the end I put some pants on and went down. They were still there, waiting for you to show. I told them they should leave a number and Id call them when you turned up. He dug in his pocket, fished out a table napkin, which he handed to me. There was a phone number written across it in Grambass lopsided, up-and-down handwriting.

What did they look like? I asked him.

Wet.

In the office I did the usual triage on the utilities bills and the usual ruthless cull on the rest of the mail, most of which is of the kind where you can tell its a scam or a speeding fine without even opening the envelope. The phone messages take longer, and some of those I had to follow up with calls of my own, but none of them were what you could call work. Not paying work, anyway. There was one from Coldwood asking me to call him, but I decided Id put that off until later in the day. There was one from Pen, telling me that Coldwood had called the house, too, about five minutes after I left.

And there was one from Juliet.

Hello, Felix. I was rummaging in the filing cabinet, but that voiceplucking on the bass strings of my nervous systembrought me upright and turned me around to face the phone as though she might actually be there. I want your advice on something. Its a little unusual, and Id like you to see it for yourself. Youd have to get over to Acton, though, so Ill understand if you say no. Call me.

I did. Juliet, I should point out, is only a professional acquaintance of mine. True, Id crawl on my belly to Jerusalem to turn that business relationship into something more torrid and sweat-streaked, but so would any other man who meets her and Id guess more than half of the women. Shes a succubus (retired): getting people aroused and not thinking straight is part of how her species hunts and feeds.

Call return didnt work, but I had Juliets number written down on a card that I carried in my wallet: like I said earlier, I almost never used it, because there was almost never any point. She stayednominallyin a room at a womens refuge in Paddington. It had struck me as odd, at first, but it made a crazy kind of sense: men had abused her and controlled her until she got out from under and devoured them body and soul. In reality, though, the room was just a place where she stored her few belongings: she didnt need to sleep, and she liked the open air, so she never spent much time there herself.

Her phone rang for long enough for me to consider giving up, but its rare enough to get a ring tone rather than the busy signal, so I held out. Its not really her phone at all: its in the communal kitchen of the refuge, shared by all two dozen or so of the residents. After a minute or so it was finally picked up by Juliet herself so my luck was in again. I made a mental note to buy a lottery ticket.

Hello?

Its me, I said. Whats the deal?

Oh, hello, Felix. Thanks for getting back to me.

Well, Im still your sensei, right? Cant leave you running around on your own out there.

This was one of the more ridiculous aspects of our relationship. Juliether real name is Ajulutsikaelhad originally been raised from hell to kill and devour me because I was asking awkward questions that a pimp named Damjohn didnt want answered. But then she decided that living on earth was preferable to going home to the arse-end of hell, so she bailed out on the job and let me liveon condition that I taught her the exorcism game. So I found myself giving a work experience placement and tax advice to an entity several thousands of years old, who if she ever got the munchies during the working day could suck my soul out through any bodily orifice or appurtenance she chose. It had been interesting. Many years from now I might even get an unbroken nights sleep again.

So is this work, or what is it? I went on, pushing those memories firmly back down into the fetid oubliette of my subconscious.

I have a commission, she said, sidestepping the question. At a church in West London. St. Michaels, on Du Cane Roadits right opposite Wormwood Scrubs.

And?

And Id like a second opinion on something.

Are you being deliberately oblique and mysterious?

Yes.

Fair enough. Ill come on over when Im done here. Is around six okay?

Perfect. Thank you, Felix. Its been a long time. I look forward to seeing you.

Yeah, I said. Likewise. Catch you later, Jules.

I hung up. Damn if I wasnt sweating. Just her voice, and I was sweating.

I had to get my mind onto another track. Remembering Grambass napkin I took it out of my pocket: the numbers were slightly smeared by raindrops from when hed passed it to me in the yard, but still legible. The first digits were 07968, so it was obviously a mobile.

I dialed.

Hello? A mans voice, hesitant and over-careful, as if he expected bad news.

This is Felix Castor, I said. You called by my office this morning.

Mr. Castor! The sudden excitement added a whole new palette of colors to the guys voice. I wish I could have that effect on some of the women I meet. Thank you for getting back to us. Thanks so much. Are you at your office now?

Yes, I am. If youd like to arrange an appointment

Well be right there. Im sorry, I mean can we come and see you now? Were very close by. Would that be convenient?

I considered a face-saving lie: its never a great idea to let a client see that youre instantly available, because they draw all sorts of inferences about your caseload. On the other hand, it didnt sound like Id be having to work too hard to sell myself here.

So, Sure, I said. Come on over.

* * *

They introduced themselves as Melanie and Stephen TorringtonMel and Steve. Nice people. I could see why Grambass fiancée, Maya, had instinctively sympathized. They both looked to be in their late thirties, well dressed and well groomed, affluent but not making a whole big thing out of it. Actually, there might have been one other thing that triggered the sympathy, and I was surprised that Grambas hadnt mentioned it. The whole of the left side of Melanies face was a purple mass of bruising, her eye swollen half out of its socket.

Stephen was tall and blond with a rich tan that could even have been natural, although he sure as hell hadnt gotten it in Harlesden. His slate-gray eyes could have given his face a hard cast, but the exp

ressionself-effacing, open, slightly nervoustook a lot of the edge off it. He wore a nicely cut dark gray suittoo nice, and with too good a hang, to have come off the rackand a sky-blue tie with a lacquered tiepin in the shape of a judges gavel. He also had a black plastic bin-liner full of something or other, clutched tightly in both hands so that he had to put it down to shake my hand. The bin-liner didnt exactly go with the ensemble, but I figured wed get to it in due course. And the handshake, which Id hoped might give me some measure of the man underneath the tan, told me almost nothing. Sometimes whatever sense it is that lets me spy on the dead lets me overhear the emotions of the living, too, through skin-to-skin contact. From Stephen Torrington I got nothing but a burning thread of determination that overrode everything else.

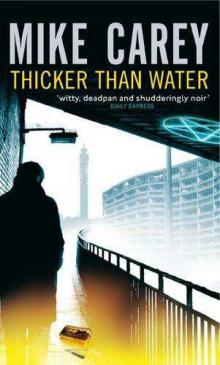

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1