- Home

- Mike Carey

Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle Read online

Vicious Circle

Mike Carey

Vicious Circle

Mike Carey

Hachette

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright Š 2006 by Mike Carey

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com.

First eBook Edition: July 2008

ISBN: 978-0-446-53760-5

Contents

Acknowledgments

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Also by Mike Carey

The Devil You Know

Alphabetically, to Ben, Davey, and Lou;

chronologically, to Lou, Davey, and Ben.

They wont stay where I put them anyway,

thank God, so either way is fine.

May the world be good enough for them.

Acknowledgments

In the UK edition of this book I thanked my editor, Darren, my agent, Meg, publicist George Walkley, desk editor Gabriella Nemeth, copy editor Nick Austin, and my wife, Lin, all of whom played crucial roles in its creation. Im thanking them again now, but this time with a Damon Runyonstyle New York accent.

And because the American edition has been through an entirely different alchemical process, Id also like to thank Grand Central Publishing editor Jaime Levine and publicist extraordinaire Lisa Sciambra, both for making the U.S. edition happen and for all of their heroic efforts during my recent ten-city U.S. book tour (which included keeping me alive and sane). They go into the box labeled people I feel privileged to have met. So do Charlotte Oria, Claire Friedman and her totally amazing family (Jeff, Jeremy, and Jacob), James Sime and Kirsten Baldock, Tad Williams, Richard Morgan, Chris Golden, Alan and Jude of Borderlands, Kristine and Jeannie and their colleagues at the Encino Barnes and Noble, and Doselle Young (whom I also have to thank for one of the most memorable games of pool Ive ever lost).

Sometimes I love this job.

One

THE INCENSE STICK BURNED WITH AN ORANGE FLAME AND smelled of Cannabis sativa. In Southern Africa it grows wild: you can walk through fields of it, waist-high, the five-fronded leaves caressing you like little hands. But in London, where I live, its mostly encountered in the form of black, compacted lumps of soft, flaky resin. A lot of the magics gone by then.

Det. Sgt. Gary Coldwood gave me a downright hostile look through the tendrils of the smoke, which curled lazily up through the cavernous interior of the warehouse, the sweet smell dissipating along the aisles of sour dust. The warehouse was on the Edgware Road, on the ragged hinterlands of an old industrial estate: judging from the smashed windows outside and the rows and rows of empty shelves inside, it had been abandoned for a good few yearsbut Coldwood had invited me to join him and a few uniformed friends for a legally authorized search, so it was a fair bet that appearances were deceptive.

Have you finished arsing around, Castor? he asked, fanning the smoke irritably away from his face. I dont know if all this tact and diplomacy is something he was born with or if he just learned it at cop school.

I nodded distantly. Almost, I said. I have to intone the mantra another dozen or so times.

Well, Jesus, you know? It was Saturday night, and I already had a heap of my own shit to cope with. When the Met calls, I answer, because they pay on the nose, but that doesnt mean I have to like it. And anyway, I figure that if you give them a little showmanship theyll be more impressed when you come up with the goods. Look, boys, I say in my own devious way, this is magic: it has to be, because its got smoke and mirrors. So far, Coldwoods the only cop whos ever called me on it, and thats probably why we get along so well: I respect a man who can smell the bullshit through the incense.

But tonight he was in a bad mood. He hadnt found a dead body in the warehouse, and that meant he didnt know what he was dealing with just yet. Could be a murder, could just be their man doing a runner; and if it was a murder, that could be either a golden opportunity or six months of covert surveillance going up in aromatic smoke. So he wanted answers, and that made him less than usually tolerant of my sense of theater.

I murmured a few variations on om mane padme om, and he kicked the heel of my shoe resonantly with his Met-issue heavy-duty policemans boot. I was sitting on the floor in front of him with my knees drawn up, so I suppose it could have been worse.

Just tell me if you can see anything, Castor, he suggested. Then you can hum away to your hearts content.

I got up, slowly; slowly enough for Coldwood to lose patience and wander across to see if the forensics boys had managed to shag any prints from a battered-looking desk in the far corner of the room. He really wasnt happy: I could tell by the way his angular facereminiscent of Dick Tracy, if Dick Tracy had joined-up eyebrows and a skin problemhad subsided onto his lower lip, forcing it out into a truculent shelf. His body language was a bit of a giveaway, too: whenever he finished waving and pointing, which he does when he gives orders, his right hand fell to the discreet shoulder holster he wore under his tan leather jacket, as if to check that it was still there. Coldwood hadnt been an armed response unit for very long, and you could tell the novelty hadnt worn off yet.

I ambled across the warehouse toward the door Id come in through, away from the forensics team, watched curiously by two or three poor bloody infantry constables who were there to maintain a perimeter. Coldwood knows my tricks, and makes allowances for them, but to these guys I was obviously something of a sideshow. Ignoring them, I looked behind the filing cabinets that were ranged along the wall to the right of the door, banged on the cork notice board behind them, which had sheaves of dusty old invoices clinging to it like mangy fur, and turned the girlie calendars over to look at the bits of gray-painted cinder block they were covering. Disappointingly, there was nothing there. No hidden doors, no wall-mounted safes, not even old graffiti.

I looked down at my feet. The floor of the warehouse was bare gray cement, but just here by the notice board and the filing cabinets there was a ragged rectangle of red linoleuma psychedelic sunburst pattern, very retro-chic unless it had been there since the seventies. Id noticed another piece, with the same pattern, underneath the desk. Here, though, there were scuff marks in the dust where the lino had been moved in the recent past. I kicked down experimentally with my heel. There was a slightly hollow boom from underneath my feet.

Coldwood? I called over my shoulder.

He must have caught something in my voiceor else hed heard the hollow note, toobecause he was suddenly there at my elbow. What? he asked suspiciously.

I pointed down at the lino. Something her

e, I said. Does this place have a cellar?

Coldwoods eyes narrowed slightly. Not according to the plans, he said. He beckoned to two of the plods and they came over at a half run. Get this up, he told them, gesturing at the lino.

They had to move the filing cabinets first, and since the cabinets were full they took a bit of manhandling. I could have helped, but I didnt want to get into an argument about demarcation. The linoleum itself rolled up as easy as shelling peas, though, and Coldwood swore under his breath when he saw the trapdoor underneath. It was obviously something he felt his boys should have spotted first.

It was about five feet square, and it lay exactly flush with the floor on three sides. On the fourth side, the hinges were sunk a centimeter or so into the surface, but it was a professional job with the narrowest of joins so no telltale lines would be trodden into the lino above. There was a keyhole on the left-hand side: a lozenge-shaped keyhole with no widening at the shank end, so this was most likely a Sargent and Greenleaf morticenot an easy nut to crack.

Coldwood didnt even bother to try: he sent two of the uniforms off to get some crowbars. With a great deal of maneuvering, a few false starts, and a hail of splinters as the wood screamed and split, they finally succeeded in levering the entire lock plate out of its housing. Even then the bolt could scarcely be made to bend. The plate stood out of the trapdoor at a thirty-degree angle, rough star shapes of broken wood still gripped by its corner screws: a wounded sentry whod been sidestepped rather than defeated. Now that their moment in the spotlight was over, the plods stood back deferentially so that the sergeant could open the trapdoor himself. Coldwood did so, with a grunt of effort because the wood of the trap turned out to be a good inch thick.

Inside, there was a space about a foot deep, separated by three vertical plywood dividers into four compartments of roughly equal size. Three of the compartments were filled with identical brown paper bags, about the size of Tate & Lyle sugar bags, all double wrapped in plastic on top of the paper: the fourth was mostly full of black DVD sleeves, but two small notebooks with slightly oil-stained covers were sitting off in one corner. On the cover of the top one, written in thick black felt tip, were the two words goods in. What the other said I couldnt tell.

At a nod from the detective sergeant, the grab-and-dab boys fished up one of the bags and both of the notebooks with gingerly, plastic-gloved hands and took them away to the desk, looking like kids at Christmas. Coldwood was still looking at mea look that said the time for teasing was past. He wanted the whole story.

But so did I. I dont prostitute my talents for just anyone, especially anyone with a rank and a uniform, and when Im dragged into a situation I know sod all about I like to play just a little coy until I find my feet. So I threw him a question by way of an answer.

Is your man about six two, stocky, ginger-haired, wearing Armani slacks and one of those poncy collarless jackets in a sort of olive brown?

Coldwood made a sound in his throat that might have been a laugh if laughter was in his repertoire. Thats him, he said. Now stop playing Mystic Meg and tell me where he is.

Tell me who he is, I countered.

Fuck! Castor, youre a civilian adviser, so just do what youre being paid to do, okay? You dont get to look at my fucking case notes.

I waited. This was my fifth or sixth outing with DS Coldwood, and wed already established a sort of routine; but like I said, he wasnt in the best of tempers right thenhence his attempt to lead me to water and then shove my head under it.

I could arrest you for withholding evidence and hindering an investigation, he pointed out darkly.

You could, I agreed. And Id wish you joy proving it.

There was a short pause. Coldwood breathed out explosively.

His names Lesley Sheehan, he said, his tone flat and his face deadpan. He deals whatever drugs he can get his hands on, plus some nasty fetish porn on the side as a bit of a hobby. Thats probably what those DVDs are all about. Hes maybe two steps up the ladder from the mules and the street runners, and he doesnt matter a toss. But he answers to a man named Robin Pauley, who wed dearly love to get our hands on. So weve spent the last six months watching Sheehan and building up a case against him because we think we can turn him. He narced before, about ten years back, to get out of a conspiracy to murder charge. When theyve done it once, youve got a bit more of a handle on them. Only now hes gone missing and we think Pauley may have sussed what we were up to.

Sheehan wont be talking now, in any case, I said, with calm and absolute conviction.

Coldwood was exasperated. Castor, youre not qualified even to have a fucking opinion on he snarled. Then he got it. Oh, he muttered, followed a second or so later by a bitter Fuck! He was about to say something else, probably equally terse, when one of the lab rats called across to him.

Sergeant?

He turned, brisk and expressionless. Always deal with the matter in hand: keep your imagination holstered like your sidearm. Good copping.

Its heroin, the tech boy said, with stiff formality. More or less uncut. About ninety-five, ninety-six percent pure.

Coldwood nodded curtly, then turned back to me.

So Im assuming Sheehans somewhere in here, is he? he asked, for the sake of form.

I nodded, but I needed to spell it out in case he got his hopes up. His ghost is in here, I said. That doesnt mean his corpse is. Ive told you before how this works.

I need to see him, said Coldwood.

I nodded again. Of course he did.

Slipping a hand inside my trenchcoat, I took out my tin whistle. Normally it would be a Clarke Original in the key of D, but some exciting events onboard a boat a few months prior to this had left me temporarily without an instrument. The boat in question was a trim little yacht named the Mercedes, but if youre thinking Henley Regatta, youre way off the mark: The Wreck of the Hesperus would probably give you a better mental picture. Or maybe the Flying Dutchman. Anyway, as a result of that little escapade I ended up buying a Sweetone, virulently green in color, and that had become my new default instrument. It didnt feel as ready and responsive to my hand as the old Original used to do, and it looked a bit ridiculous, but it was coming along. Give it another year or so and wed probably be inseparable.

I put the whistle to my lips and blew G, C, A to tune myself in. I was aware that all the eyes in the room were focused on me now: Coldwoods expressionless, most of the others bright with prurient interestbut one of the uniformed constables was definitely looking a little on the nervous side.

The trouble with what I was about to do was that it doesnt always work: at best its fifty-fifty. Theres something about a rationalistic world view that arms you against seeing or hearing anything that would contradict itlike mermaids, say, or flying pigs or ghosts. Overall about two people in three can see at least some of the dead, but even then it depends a lot on mood and situation, and in certain professions that ratio drops to something very close to zero. Policemen and scientists cluster somewhere near the bottom of the league table.

I didnt know what I was going to play until I blew the first notes. It might have been nothing much: just the skeleton of a melody, or an atonal riff with a rough-hewn kind of a pattern to it. It turned out to be a Micah Hinson number called The Day Texas Sank to the Bottom of the SeaId seen Hinson perform at some café in Hammersmith, and I found something powerfully satisfying in the lilting harshness of his voice and the hammering, inescapable repetitions of his lyrics. But even without that, the song appealed to me for the title alone.

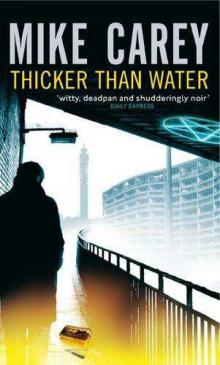

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1