- Home

- Mike Carey

The City of Silk and Steel Page 24

The City of Silk and Steel Read online

Page 24

Zuleika ignored the racing of her heart and spoke loudly the words she had prepared.

‘Great djinni. We are women. We plan to take the city of Bessa for ourselves, by guile and by arms. I want to know if we can succeed, and how best to achieve it.’

An urge came over her to beg for strength, for wisdom or for weapons that might outweigh Hakkim’s forces. She bit it down and said nothing more.

The whirling combat did not falter, nor did their attention on her. Zuleika stood and bore it. At length a cry came from all of them at once, like a battle shout.

What you need, you must take from each other!

Zuleika and Gursoon were no longer at her sides. Rem was alone, as she had known she would be. Not that she had ever foreseen this moment: the djinni may grant power, but not over themselves. Even her memories of them, of that first visit, were indistinct: their monstrous, shifting figures, their grindstone scrutiny, and worst of all that final instant of what seemed like pity. She had not consciously resolved that she would never go back there. Until three days ago, the very possibility had been unthinkable.

The sunset was bloody at the edges of her vision, cut off on all sides by the rock wall. Then it was dark, and the huge shapes ahead of her might be moving, might be only stone. She would not go forward to meet them. She hunched down on the rubbled ground, arms tight around her knees.

It was very still. But there was a breeze on her face; a night bird called somewhere behind her, and after a while she dared to open her eyes. She could see a little way into the darkness now. She made out a cluster of tall pillars, and among them dim lights and moving human figures. No-one seemed to notice her.

She stood up and took a step towards them, or perhaps the place moved around her. The pillars were the trunks of trees, she saw now, in one of those parts of the world where trees grew thickly together: a forest. The patches of yellow light were fires, built in dugouts or confined in clay pots so as not to catch on the dry leaves underfoot. And crouched over the nearest was a woman, who looked up at her.

She smiled and raised a hand, with an air of such calm familiarity that Rem’s first thought was, I’m looking at myself. Myself some ten years from now. The idea both excited and terrified her: in all her visions she had never seen her own face. But this woman’s eyes were surely too light, her face too broad and flat. She nodded at Rem and indicated a spot on the ground beside her: Come and sit down.

Close to, she might have been a beggar, unkempt and clothed in a patchwork of brightly coloured rags. Another pile of rags behind her looked like bedding. A sharp reek came off her, sweat and wood-smoke. But her eyes were clear and steady, and she looked at Rem with an encouraging air, as if expecting her to say something. When Rem stayed silent, she shrugged and turned back to her fire pot.

Rem had no words, no energy now even to wonder. The terror that had gripped her stomach was uncurling, leaving her shaken and empty. She sat by the companionable stranger in silence, not thinking, and listened idly to the scrape of her stick as she stirred up the coals. Around them other figures went about their own errands. She heard men’s voices, harsh laughter and the clink of metal. And abruptly, a barked command. The woman seemed to feel Rem’s shudder, and looked up before she spoke.

‘Is this an army camp?’ Rem asked her.

The other nodded. ‘But they won’t trouble us,’ she said. ‘I set up at the edge of camp and keep quiet, and they leave me alone.’

The words were dully familiar. They were what Rem’s mother had drilled into her through her childhood in the marketplace: don’t draw attention to yourself. It was how she had tried to live in the library, until attention had found her and pinned her out for the crows to eat. It was how her companions had lived, she thought, even Zuleika. You could be a servant or a plaything, or you could keep your head down and hope to stay unseen. She was unprepared for the anger that filled her. And she knew, suddenly, what it was that she must tell this beggar woman.

‘It won’t always be like this,’ she said. ‘We’ll make it work somehow. There will be a city ruled by women, where no-one has to hide.’

Her voice had risen, but the other woman did not seem alarmed, despite her advice to keep quiet. She laughed. ‘But that’s a story!’ she said. ‘Or old history, anyway. I read about it.’

She rummaged through the heap of rags behind her and took out something: a book. ‘It’s a good story,’ she said. ‘But right now . . . well, we have to deal with what’s before us. The important thing is to help each other.’

Rem had seen books like this in visions, but she had never held one. It was a bound volume: not a scroll like those in the library at Bessa, but pages sewn together and enclosed in a cover of soft leather. There might be nothing like this in the world for another hundred years. The woman was holding it towards her as if inviting her to take it, and Rem was seized with longing to have this thing for herself: to feel the weight of it in her hands and turn the smooth pages at her leisure; to read her own story, every word of it. But she had nothing to give in exchange.

‘Maybe one day,’ the woman said. ‘If all of us give what we can.’

It was growing darker. Rem knew she must offer something in return for the gift; she felt through her clothing for anything she had – a pin, perhaps or her writing stylus. But the movement shook her loose. The book was no longer in reach. The woman’s face fell away, friendly, a little puzzled. She spoke again: maybe a farewell, but Rem could not hear the words. There was solid rock in front of her, and other figures, a babble of voices in the remains of the red light.

It was only reasonable, Imtisar thought, that the djinni should take the form of great caliphs and queens – they emerged in procession out of the dark hole, and the splendour of their jewels, their clothes, lit up the dry and barren place like little fires.

But something about them was not right. The slender lady with the emeralds: her face was beautiful, but the skin had an odd shimmer, as if clad in scales. The man with the golden beard smiled to reveal a suspicion of tusks, or fangs. And the lord in the velvet robe, so magnificently tall: was that a tail flicking beneath the purple hem?

They fixed their royal gazes on Imtisar and on her alone. And at once all the fine words she had rehearsed flew out of her head, and she was left barely able to catch a breath. But she had to say something.

‘What do we do?’ she stammered. They looked down at her gravely, not answering. And for an instant she saw that flick of a tail again, the horns not quite concealed by a jewelled turban, the queen stroking the edge of her robe with a taloned claw. They were mocking her, she thought with a flash of anger, and this time the words came without hesitation.

‘Is that it? Must we follow this lunatic plan? All I want is our safety. For all of us. To live free of fear and poverty. Is that too much to ask?’

They smiled then. The faces were more than ever those of boar, lion and snake, but the same smile was on every one. The tall man with the tail spoke for all.

There is no safety, he told her. You may have freedom, if you choose it. But you must give something, and take something in return.

Issi could never remember later how the djinni came to him, nor quite what they looked like, nor how they sounded. A gust of sand blew up around him as he entered the valley, stinging his face so that he had to bend his head and squint at the path. Imtisar, just ahead of him, seemed not to notice. But the wind rose. In a moment he was surrounded by a dust storm, cutting out sight and sound.

Issi had encountered enough desert storms to know what to do: he threw his cloak over his head and stood still, only throwing out an arm to brace himself against the rock wall. But the wall was not there – all his groping failed to discover it – and at the same moment the noise of the storm vanished. He was blind and deaf, with no point of contact to the world.

In a sudden panic he threw off the cloak. The storm still whirled all around, but no stinging grains hit him. The noise had receded to a distant buzzing. There w

as nothing else to hear, nothing to see. But as he peered through the dust cloud for any sign of his companions, he could make out shapes. They might have been angels: winged giants, so far off he could barely see them through the storm. In another moment they seemed as small as insects, buzzing almost around his head. They are the djinni, he thought.

There seemed no way he could make them hear him, but he had to know the answer. He cupped his hand and shouted through the churning motes. His voice came back to him as less than a whisper.

‘My wife and sons, are they well? Will I see them again?’

And miraculously, an answer came, buzzing in his ears with the storm:

They are alive, and remember you.

‘Please,’ Issi begged the insect voices. ‘How can I get back to them?’

This time his own voice sounded so faint he thought the djinni would not hear. But their reply came stronger than before.

Make exchange with the boy behind you.

The storm stopped as suddenly as if it had never been. Crouched behind him, wide-eyed and trembling, was Jamal.

It had not been a whim to follow them. When it became clear that he was not to be included in the party, he had already filled the largest water skin he could find and hidden it with a blanket under rocks at the western edge of the camp. He had taken a bag for food too, but had not been able to fill it: just the morning’s bread, and a double handful of dried fruit hurriedly snatched from the stores, for which he risked humiliating punishment if caught. There was no time to get more. He watched them leave just before sunset and waited for his opportunity. When everyone around him was busy with Farhat’s chores, it was easy enough to slip into the darkness.

For almost as long as he could remember Jamal had longed to be older, had fretted about his small size and lack of strength, so that they all ignored him and treated him as a child. But now, moving unseen behind the chosen five, matching their footsteps with his own, keeping just within earshot, he revelled in his own lightness and speed. When they finally stopped to sleep he moved a little further away and dug himself a hollow in the warm sand, feeling, as he wrapped himself in his blanket, that he could have gone on for much longer.

He woke chilled and stiff in the darkness to the sound of their voices, and scrambled to his feet: they were moving on already. He trudged after them as the sun rose at their backs. When the sun reached its height he regretted that he had not brought a scarf for his head, or any kind of tent. The adults, his quarry, made a shelter of three of Issi’s light wood poles and a thin cloth to hide from the worst hour of the heat. Jamal had to huddle beneath his heavy blanket, holding it away from his face with his knees and trying not to move.

Many times during the next two days he thought about calling out, running to Zuleika and the others and announcing that he was joining them. They had come too far already to turn back, and too far to send him back alone. But something always prevented him: pride, perhaps. At other times he wondered why no one had simply turned around and seen him. But not one of the five looked back, or if they did it was in blindness. All their attention was fixed on what lay ahead; Jamal’s too.

By noon on the third day his water was gone. It came to him that he might die now if he did not call to the five ahead, but he kept on in silence, and they did not turn. As the day wore on he realised he had no more voice to call.

Towards evening he passed a rock that he thought must be the Hill of the Hand. In some of the tales pilgrims had found water there, and he thought he could hear it trickling. But he had fallen too far behind and the sun was nearly down: there was no time to waste in searching. Afterwards, he thought, and went on into the ravine.

He saw his father there, fighting with Hakkim Mehdad. Just past the stone spikes at the entrance they stood, locked together and swaying, their hands around each other’s throats. The sultan was dressed as Jamal had last seen him, in his silk chamber-robe; his bald head gleamed beneath the setting sun. Hakkim Mehdad was all in black, his head swathed in a black scarf. Jamal had never seen the man’s face; all that was visible of him now was his eyes, which glowed like those of a wolf at night.

His father turned his head and nodded to Jamal, then went back to throttling his enemy. With a cry that caught in his throat, Jamal ran to help him.

His way was blocked. Where his father had been there was now an army: countless stern-faced men, their spears all pointing at his heart. They did not attack, but stood waiting for him to speak. So this was the moment, but Jamal had no voice. Nevertheless, he made his demands, shaped with his lips and hurled towards them with all the breath he had, though his throat made no sound but a hoarse gasp.

‘I want my kingdom back. And I want to avenge my mother and my father. Help me take back my rightful place!’

They heard him. At least, they seemed to answer. A voice came to him; he could not tell if it was one or many.

Some of your desires you will gain, it told him. But you must offer something. Now!

The last word was like a thunderclap. It wiped out the army, the spears and banners, like mist in the sun. Jamal was kneeling on bare sand, looking at bare rock. And beside him, gazing down with horror and amazement, was Issi.

NOW, the djinni said, heavy as a great book closing, and vanished. The six gazed at each other in the empty ravine, in the last light.

‘Jamal!’ Gursoon exclaimed. ‘How—’

‘Not now,’ Zuleika cut in. ‘What did you hear? What did they tell you?’

‘That we need gifts . . .’ Gursoon’s voice was doubtful.

‘They told me I must give something,’ Imtisar said. ‘And take something.’

‘Make exchange . . .’ Issi said. ‘But what does it mean?

‘It means the gifts come from us.’

It was Rem who spoke. She had been sitting hunched, pressing herself against the rock wall furthest from the cave, and her voice was muffled. ‘I think . . . we have to give gifts to each other. Now, before the sun sets.’

‘What gifts?’ Zuleika seemed almost indignant. ‘We have nothing here!’

‘Maybe when we get back . . .’ Gursoon began.

‘No!’ Rem was suddenly on her feet, and shouting with desperate urgency. They turned to her in amazement. Her face was paper-white, the black tears marking it like bars.

‘No. It has to be now. That’s how they work . . . Whatever you have, whatever you have with you, give it to someone. I don’t know why. But we must do it, before it gets dark.’ She felt inside her tunic, pulled out a reed pen and pressed it into Zuleika’s hands. ‘Like this. Here. This is for you.’

Gursoon nodded and pulled a ring from her finger, holding it out to Imtisar. The other woman, after some hesitation, reached up to take a comb from her hair. But as she took Gursoon’s ring she started and tried to give it back.

‘I can’t take this! This is Bokhari’s ruby. It’s worth a fortune! Give me something less – that little silver ring you have . . .’

‘This is what I’m giving you,’ Gursoon said firmly. Take it, Imtisar, with my blessing.’ She turned away. Imtisar gazed at the ring with appalled delight.

Issi had been patting down his clothes, finding nothing detachable. At length, with visible reluctance, he took something on a string from around his neck.

‘It’s the key to the sultan’s stable yard,’ he said to Jamal. ‘Just don’t lose it.’ Jamal had nothing to hand him in return but an empty water skin, which Issi took a little sourly.

Rem turned to Zuleika, who had not moved since she had accepted the little pen. It still lay in her hand, narrower than her smallest finger. She looked down at it as if uncertain what to do with it.

‘I have nothing to give you,’ she said. ‘There were only my knives, and I left them on the ground, back there. Shall I go now and get them?’

‘No!’ Rem was adamant. ‘It must be here and now.’

They held each other’s gaze for several heartbeats Then Rem looked down at the pen in the other woman’s han

d.

‘The lessons I gave you,’ she said. ‘Do you remember them?

Zuleika made a movement of irritation, suppressed it, nodded.

‘Then give me a word.’

Rem blinked fiercely, and the black tears welled again. She reached to take the pen from Zuleika’s hand, dabbed the point into the black stream beneath one eye, and returned it. She held out her right arm, turning it to expose the pale skin below the elbow.

‘Just here. Write a token for me.’

It seemed to take them a long time. Zuleika, so sure and graceful with all the tools and motions of her chosen trade, was clumsy with the little slip of wood, handling it as if she were afraid of causing damage. She wrote her name in large, spiky script, separating each letter. The last one ended in a round blot. They stood together, Zuleika still holding Rem’s arm, and watched the word dry.

‘Is it enough?’ Zuleika asked at length.

Rem nodded, still gazing down at her arm with its new mark.

‘So what do we do now?’ Zuleika said.

Rem looked up. Her face was still white, but the black tears no longer welled from her eyes; their tracks were drying. For the first time in days, she smiled.

‘It’s done,’ she said. ‘Now we can go home.’

Reading Lessons, Part the Second

Let’s back up a little.

After I spoke those words, ‘We take back Bessa,’ everything started moving in double time. The council of war, the visit to the djinni: the flood of revolution engulfed us with such astonishing speed that most of us never paused to consider the precise nature of the current that swept us along. But it is part of my gift, and my burden, always to consider the current, and I would neglect the responsibilities of both if I avoided it now.

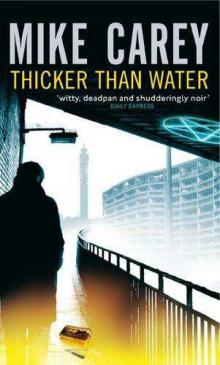

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1