- Home

- Mike Carey

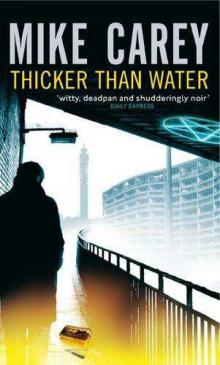

Thicker Than Water Page 24

Thicker Than Water Read online

Page 24

As exit lines go, it wasn’t all that punchy, but it left me staring at the door long after it swung to behind her.

Wounds. Points and edges. And one long, lonely fall to the ground. Or two. There would have been two if I hadn’t stopped Bic from stepping off the ledge the other night.

What the fuck did it all mean? And where did I go to fill in the gaps?

14

The next day dragged on like a wounded snake across a barbed wire entanglement. It still hurt me to breathe, and I still couldn’t walk very far without resting up every few steps to let my lungs reinflate. I could have checked myself out of the hospital, but I was stiff and sore enough to find the prospect daunting, and I wasn’t sure yet where I was going to go. Something was crystallising in my mind, but it was taking its own time coming.

A junior intern changed the dressing on my ribs, giving my fingers a cursory examination along the way. I asked her how soon I could expect to play the tin whistle again: she looked at me like that was meant to be a joke, and then suggested that I take up comb and paper. Later on, a nurse came round to inspect my stitches and declared that they were doing nicely.

‘Then I can expect to leave soon?’ I asked.

‘Oh yes, I should think so. We’ll be needing the bed for someone else.’

‘Tomorrow?’

‘When the doctor says.’

On and off through the day, I read through Nicky’s downloads and transcripts, looking for insights that didn’t seem to be there. Nurse Ryall’s hunch about the wounds played out strongly across the board. The dense, dry prose was full of people puncturing each other and themselves, carving and slicing and severing human flesh in every way imaginable. And in the middle of all this, one boy jumped off an eighth-storey walkway and kissed the concrete.

Or rather, not in the middle: Mark Seddon’s death predated everything else on Nicky’s list. It was as though he’d opened the door to something that had come spilling out like toxic waste across the entire estate.

Feeling restless, and enervated from doing nothing else but lie or stand or sit up on the ward, I went for a walk around the rest of the wing. Inspiration didn’t come, and if anything the ghosts with their alarming array of stigmata and their disregard for walls and floors were even more of a distraction than the kid with the headphones. But it felt good, in some obscure way, to be moving - even if I was going round in circles.

In the evening, when I was sitting up in bed again with the notes spread out in front of me, chewing over random horrors until they were bland and flavourless, I had a visit from Detectives Basquiat and Coldwood. Basquiat said she wanted to ask me a few more questions. She was carrying a black leather document wallet which looked disturbingly full of something or other: also a micro-tape recorder which she switched on and put down on my bedside table. Gary seemed to be there purely to act as chaperone, which probably didn’t bode well for me at all.

‘What happened to your face?’ Basquiat demanded, after she’d cued in the tape with date, time, people and place. There was a glint in her eye that was far from solicitous: she was interested because she didn’t believe there was an honest way to come by bumps and bruises on such a heroic scale unless you were in police custody at the time.

‘Cut myself shaving,’ I said.

Gary opened his mouth, probably to tell me to do myself a favour and stop pissing about, but Basquiat signalled for him to let it pass. ‘I’d like to come back to the question of your movements on the night when Kenneth Seddon was attacked,’ she said.

‘What I told you last time still stands,’ I said.

‘Meaning that you were at home with your landlady, enjoying a takeaway curry and a few cans of Special Brew.’ She was only so-so as a poker player: she kept the edge out of her voice and her face as expressionless as the keyboard player in Sparks, but there was a set to her shoulders that betrayed an underlying tension.

‘I don’t drink Special Brew,’ I temporised. ‘It was probably Theakston’s Old Peculier. Or maybe some kind of Belgian blond—’

‘You were at home,’ Basquiat repeated, cutting across me. ‘You didn’t go out the whole night until Detective Sergeant Coldwood came to collect you at four a.m.’

Backed into a corner, I gave a straight answer. Too bad it had to be a straight lie. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘To the best of my recollection, I didn’t go out.’

‘Not even to pick up a pack of cigarettes?’

‘I don’t smoke.’

‘Nicotine patches, then.’

‘I don’t smoke because I never got started.’

‘Dry-roasted peanuts. Salt-and-vinegar crisps. A DVD rental.’

‘No, no, and no.’

She nodded, satisfied. ‘And your landlady will corroborate this?’

I looked over Basquiat’s head at Coldwood, who was studying Van Gogh’s ever-cheerful sunflowers and didn’t meet my eye.

‘Ask her yourself,’ I suggested.

‘In good time. I’m just asking you if you’re happy with your alibi, from a structural point of view. Is it fit for purpose, Castor? Will it take the strain?’

I looked her in the eye. ‘Alibi?’ I repeated, as if it was a word I’d never heard before.

‘If you were down in South London that night, you might not want to tell us about it.’

‘I can’t even remember the last time I was south of the river,’ I said. ‘Well, I mean before this thing broke.’

‘Days? Weeks? Months?’

‘Months. Must have been.’

‘How many months?’

‘At least six.’

Basquiat didn’t answer, but she did finally unzip the document wallet. On top of the papers inside was a small stack of A4-sized photographs, one of which she held up for me to see. It was a grainy enlargement from a badly framed original, taken at night without a flash but with some kind of light-enhancement technique that made everything into an over-contrasted soot-and-chalk cartoon. It showed a white Bedford van, stationary at a traffic light. Someone had drawn a ring around the registration plate in thick black marker.

Basquiat flicked that photo down onto my bedsheets like a blackjack dealer, revealing the second one behind it. This was a zoom in from the previous image, focusing on the driver. He was hunched over the wheel, squinting sideways at the red light that had stopped him in his tracks as though he could make it turn green just by facing it down. The resolution was surprisingly good: it was me at the wheel, beyond any reasonable shadow of a doubt. Basquiat dealt me that one too and showed me the third: a close-up on my face, the image looking a little washed out and raggedy-edged this time. So did I, for that matter. My mother would have said ‘Poor Felix!’ by automatic reflex.

‘Speed camera?’ I asked, conversationally.

‘Do you see any motion blur? Bus-lane camera, Castor. St George’s Road, Elephant and Castle. You tried to overtake a truck in the left-hand lane and got caught by the red at just the wrong moment. This was three weeks ago. The night of the third. ‘

I handed her the first two photos back. Might as well keep the whole set together.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘You got me. Being vague on dates isn’t evidence of murder, though.’

‘No, just of having something you needed to lie about. We traced the reg back to a dodgy little runt in Cheshunt. Name of Packer. The worst kind of dodgy little runt, in a lot of ways - the kind that’s on parole, and caves in at the first whiff of a search warrant. He was telling us first of all that he’d hired the van out to a Greek gentleman named Economides. But I reminded him that every time a lag on probation actively colludes in a criminal enterprise, a fairy dies. After that he was only too happy to put your name in the frame.’

Thanks, Packer, I thought sourly. I owe you one, mate. But hard on the heels of that thought came the twin realisations that he didn’t have any choice and it didn’t make any difference. Once they had the van they had as much supporting evidence as they liked. My fingerprints would be all over it in a

ny case. Basquiat had found a smoking pistol - but it was the wrong pistol, and the wrong crime. Looking for evidence that I’d tried to murder Kenny, she’d found the trail that linked me to Rafi’s escape.

I waited for her to tell me I had the right to remain silent, but she didn’t seem in any hurry to wrap this up.

‘So what were you doing in Elephant and Castle at half past midnight?’ she asked sarcastically. ‘Getting into line early for the tropical house? Or crossing over into South London by a route that wasn’t the shortest line between your gaff and Seddon’s?’

This was bad. Worse than bad, probably. At the Stanger we’d been careful not to park anywhere within range of the one visible security camera, but the nurse on reception had seen the van and presumably the description was right there in the police report. I was caught between a rock and a hard place. The only way I could get myself off the hook for attempted murder was to put myself on a different hook labelled grand theft Ditko. Either that or pray that Kenny would come out of his coma and agree to be a character witness. Under the circumstances, dumb insolence was the closest thing to a strategy I could scrape up.

Basquiat didn’t mind. She was keeping her end of the conversation up very well without me.

‘So we’ve got you in the vicinity of the Salisbury Estate,’ she summarised. ‘Admittedly, some weeks before the attack on Kenny Seddon, but - to make things more interesting - in a van you took the trouble to hire under an assumed name. And we’ve got you lying about it in evidence freely given to an investigating officer - both now and when I asked you the first time down at the Cromwell Road nick. Are we having fun yet, Castor? Because it gets better.’

I looked at Coldwood again. This time he met my gaze. He touched his lips, which were closed, presumably to indicate that I had nothing to gain by running my mouth off here. It was a fair point, but not one that I needed coaching in.

‘You were seen on the Salisbury Estate,’ Basquiat went on. ‘Two nights ago. Barely twenty-four hours after you were released from police custody. I’ve got positive ID from two separate sources. I ought to be embarrassed about how easy you’re making this, but hell, these days it takes a lot to make me blush. Now tell me what you were up to, and maybe when you come out on the far side of this you won’t be quite old enough to claim your pension.’

Her tone had become even colder and more clipped in the course of this speech, and she was leaning forward, her face just a little too close to mine. Two separate sources? I thought irrelevantly. Was one of them Catholic? Was the other Gary? Where did the Pope shit these days, anyway?

‘I was looking into the attack on Kenny myself,’ I began, ‘because it seemed pretty likely that I was going to end up in the frame for it—’

‘You built the bloody frame,’ Coldwood growled - his first contribution to the proceedings. I knew what he meant. I couldn’t have put myself in a shittier position if I’d been trying. But hope springs eternal, especially when you’ve got nothing else to fall back on.

‘Kenny was sending me a message,’ I said. ‘The words on the car windscreen were like - the last throw of the dice. He wanted me to look at what was happening down on the Salisbury, so he did the only thing he could think to do as he was bleeding out.’

‘And you felt like you had to honour his last request?’ Gary concluded. Basquiat clenched her fists and swung round to give him a look, but she was too late to stop him from spoiling her game plan. I took the sucker punch to the chest, not to the chin.

‘Kenny’s dead,’ I said, feeling a momentary sense of vertigo.

‘About three hours ago,’ Basquiat confirmed. ‘So it’s not wounding with intent any more, Castor. It’s murder. And this is your last chance to level with me about your part in it.’

‘My part?’ I couldn’t make my brain work, and I couldn’t figure out what her game was - the way she was playing this. But my hopes of Kenny coming round and explaining how all this was just some amusing mistake had just gone up the Swanee. ‘Basquiat, for the love of Christ!’ I said, almost pleading because I really felt like I needed not to be arrested right now. ‘I didn’t kill Kenny. You know I didn’t. You’ve got two other men’s prints on the fucking razor.’

‘But the razor wasn’t the murder weapon,’ she reminded me grimly, her face still almost shoved into mine. ‘The last blow - the one that counted - was struck with a short knife, none too sharp, that we haven’t been able to retrieve yet. What’s the fascination with the Salisbury Estate, Castor? Why do you keep going back there, if it’s not to get paid or cover your tracks or coach someone down there through their story?’

‘I was checking the place out,’ I persisted doggedly, ‘because Kenny’s message—’

‘And you called in some back-up of your own, didn’t you? I almost forgot that part. But you were smart there, at least. Kept it in the family.’

‘In the family?’ I echoed, missing her point for a moment. Then I realised what she was talking about and felt sour anger flare in my stomach like a progress report from a perforated ulcer. ‘Yeah, right. Of course. I teamed up with my brother, who’s a fucking priest, and we carved Kenny up because he stole our football back when I was ten. Basquiat, Matt wasn’t even with me when I went to the Salisbury. He was there by himself, under orders from another priest named Thomas Gwillam. If you want to know more, look him up in the Yellow Pages under rabid religious conspiracies.’

‘The two of you were seen at the Salisbury together.’

‘Because we were both there for the same reason, I suppose. I mean, because of what happened to Kenny. But we didn’t arrive together and we didn’t . . .’ I faltered for a second, lost my thread, because I was listening to my own words and I could see, very abruptly, how little sense they made. Everything was tied together. It had to be. But maybe I was wrong in putting Kenny at the centre of it. When I first saw Gwillam on the walkway at the Salisbury, it was before any word of Kenny’s death could possibly have got out to him. And the first thing he’d done, as far as I could make out, was to knock on the Danielses’ door.

Incised wounds. Puncture wounds. Bic didn’t have either kind. And I suddenly realised that that might be the point.

Basquiat was still looking at me expectantly. ‘Didn’t what?’ she prompted.

‘Didn’t anything,’ I muttered. ‘We ran into each other, we talked, and then we went our separate ways.’

‘You ran into each other.’ Basquiat didn’t even need to inject any sarcasm this time: the words just hung there, limp and ailing in the unsympathetic air.

‘I didn’t call Matt to the Salisbury,’ I said.

‘So he was there for reasons of his own.’

‘Obviously.’

‘Before Kenny Seddon was attacked, or after?’

‘Like I said, ask Gwillam. There’s a church-based group called the Anathemata Curialis—’

At this point the main door of the ward swung open and Charge Nurse Petra Ryall walked in, wheeling the meds trolley. She immediately looked across at the little group by my bed, and her gaze lingered. Basquiat’s power dressing is multifunctional, but you couldn’t mistake Gary for anything but a cop.

‘Find Gwillam,’ I suggested again. ‘Ask him about all this. Matt is part of whatever he’s doing. You ought to be able to get chapter and verse on that from your two fucking sources—’

Basquiat stood up, so abruptly that I was taken by surprise and stopped in mid-curse. ‘I’ll do that,’ she said. ‘And in the meantime, I suggest you don’t leave town. Can you promise me that, Castor? Because if I have to come chasing after you, when I find you I’ll nail your balls to the table to make sure you stay where you’re put.’

I stared at her, mystified. The absence of handcuffs, verbal cautions and statutory phone calls caught me so far off balance that all I could think of to say was ‘What?’

‘Stay at your regular address,’ Coldwood interpreted. ‘Or check with us before you go anywhere. We’ll be in touch again soon.’

‘Ending interview at ten-sixteen a.m.,’ Basquiat said. She picked up the tape recorder, turned it off, and slipped it back into her pocket. ‘Very soon,’ she confirmed, and stalked away without even blowing me a kiss. She stopped and looked back, though, when she realised that Gary wasn’t following her. He was still loitering by the sunflowers.

‘I need a minute,’ he said.

‘Off the record?’ Basquiat’s tone was dangerous.

‘Off the record.’

‘No.’

‘How exactly are you going to stop me, Ruth?’

Her eyes narrowed. ‘By telling you no,’ she said. ‘I’m senior officer on the case and I conduct the interviews.’

‘This isn’t an interview.’

‘Then send him a bloody postcard.’

Gary waited her out. In the end she made a gesture of disgust and walked on through the door, pushing the meds trolley out of her way. Petra Ryall muttered something that could have been either an apology or an imprecation, but Basquiat wasn’t listening in any case.

I looked up at Gary, and he looked down at me. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a few folded sheets of paper, which he handed to me wordlessly. I looked a question at him.

‘Mark Seddon’s autopsy report,’ he said. ‘Only he’s down as Mark Blainey. They went by the birth certificate.’

‘Bloody hell.’ I picked up the sheets and stared at them with a certain wonder. ‘Thanks, Gary. I wasn’t expecting this.’

He didn’t answer, but it was clear from his face that there was something else on his mind, so I waited for him to spit it out. ‘Fix, I took a hard fall for you last year when you had me looking into that crematorium thing. And you never really told me what it was all about.’ It wasn’t an accusation. His expression was sombrely reflective.

‘A lot of people ended up dead,’ I reminded him. ‘I didn’t want to put you in an awkward situation.’

‘You never apologised to me for getting my legs broken, either.’

‘I said sorry in my own way, Gary.’

‘By never referring to it again and dodging the subject whenever I brought it up.’

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1