- Home

- Mike Carey

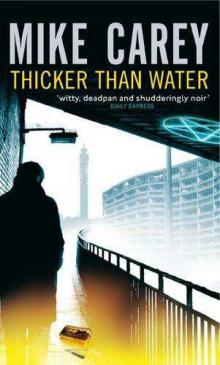

Thicker Than Water Page 22

Thicker Than Water Read online

Page 22

‘Felix Castor!’

The voice was acerbic, angry, the emphasis very pronounced. I came out of my grim reverie and found myself looking up at the nurse, who was standing at the foot of my bed with my chart in her hand. And I understood her tone immediately, because she already knew me. But not by that name.

‘Nurse Ryall,’ I said, weakly. ‘Petra.’

The redhead quirked her head and flashed her eyes meaningfully. ‘Detective . . . Basketcase, was it?’

‘Basquiat,’ I said. ‘Would you believe I’m here undercover?’

She thrust the chart back into its holder with more vigour than was necessary. ‘It doesn’t matter what I believe,’ she said. ‘That bloke upstairs was under police guard because someone had tried to murder him. I don’t know how you got in there, but I’m going to report it to the shift registrar and let her decide what to do with you.’

I tried to jump up out of the bed to head her off, but the pain relief I’d been given was working too well for that. I slumped back down onto the banked pillows and she turned on her heel.

‘They’ll want to know why you didn’t ask to see any ID,’ I called hastily.

Nurse Ryall hesitated, and then turned back to me with a flush of anger on her face.

‘You told me—’ she began.

‘No, you just made an assumption,’ I countered. ‘And I played up to it. Look, give me a minute to explain. I can’t stop you from reporting me, but if you do we’re both going to be in the shit for nothing.’

She stared at me wordlessly for a long time. I held on for the answer, keeping my stare locked with hers.

‘Go on,’ she said at last, her tone verging on grim.

I pointed to the chair that Nicky had left vacant. ‘Why don’t you sit down?’

‘Because you said you’d only need a minute.’

‘That was poetic licence. I’ll need ten.’

She consulted the watch she wore pinned to her chest. ‘I don’t have ten minutes,’ she said. ‘I’m on ward rounds.’

‘Then come back later. Seriously, there’s an innocent explanation for all this.’ If you stretch the word ‘innocent’ out to its functional limits, I thought to myself, and then knot it into a balloon sculpture. Nurse Ryall looked unconvinced, but after another painfully overextended pause she finally nodded.

‘All right,’ she said. ‘In two hours, when I’m on my break. But it had better be good.’

‘I’ll see you then,’ I confirmed, feeling weak with relief. Well, feeling weak generally, if the truth be known, but relief was in the mix.

Nurse Ryall stalked away, accompanied by the concatenation of her heels like the hoofbeats of apocalyptic horsemen.

I tried to wade into the haunted depths of Nicky’s paper trail again, but my attention was shot to hell. Giving up, I thought about the few things I thought I knew and the many, many more about which I was totally in the dark.

Something - quite possibly something demonic - was haunting the Salisbury estate. And the ripples seemed to be spreading in the form of an increase in violent acts of every kind. Even in that cautious formulation, I was naggingly aware that there was something I was missing. But my mind was too distracted by drugs and discomfort to pin it down.

Kenny, who had a ringside seat from the eighth floor of Weston Block, and whose own stepson was one of the victims, had tried to warn me about something. Or at least, while dying in his car of an overdose of slash wounds he had written my name on his windscreen in his own generously flowing blood. He’d got my attention, at somewhere considerably over the market price.

And the Anathemata Curialis, an ultramontane Catholic sect dedicated to the overthrow of the risen dead and undead, was now doorstepping the flats on the Salisbury - raising subjects that Jean Daniels hadn’t wanted to discuss with me. I’d tried to step in on that dance and had got myself well and truly bounced by the big man, Feld. Clearly this gig was invitation only - and the invitation seemed to have extended to my brother Matt, even if it hadn’t quite reached all the way to me.

A consultant on his late-evening sweep was working his way down the ward, looking at charts without enthusiasm and making a few observations now and again to his retinue of admiring interns. The procession stopped at my bed briefly, but seeing that I presented nothing more interesting than a punctured pleura and a few bumps and bruises, there was nothing to keep them.

Bored and restless, I tried again to make sense of the paperwork. It wasn’t just the unappetising format that was making it hard for me, it was the content, too. It was like looking through a tiny, smeary window into one of the circles of Hell. A drunken fight where one of the combatants had pulled a can opener instead of a knife, and had put it to a use not too far removed from the one it was designed for; a late-night duel with sharpened pool cues; home-made shurikens and caltrops, piano wire and cheese graters . . . Okay, we were talking about a span of well over a year, but were the residents of the Salisbury so much in love with blood that they spent their time devising new implements for tapping it? The sheer invention on display was disturbing in itself, although it paled next to the terse, unreflective case histories. This wasn’t right. Nothing here was right.

A clitter-clatter of heels jolted me out of my reverie, and I looked up to see Petra Ryall approaching, grim-faced. She looked around, her expression defensive and resentful, but the consultant and his teenage sidekicks had moved on to pastures new, the fat man and the twitching guy were asleep and the kid was lost in his own world of high-fidelity audio input. She pulled up the chair, sat down, glanced at her watch once to note the start time.

‘Ten minutes,’ she reminded me.

‘Okay,’ I agreed. ‘Well, for starters, I’m not a detective. I’m an exorcist.’

That got a sceptical eyebrow-flash, but no other response. Nurse Ryall stared at me, waiting for more.

‘I bind and banish the dead,’ I translated.

‘How?’

‘With a tin whistle.’ I spoke over her next question, because I’ve had this conversation a lot of times with a lot of people. ‘No two exorcists do it the same way. It’s music for me. For someone else it could be pentagrams or incantations or automatic writing or interpretative dance. It doesn’t matter. You make patterns, and things happen.’

‘What sort of things?’

‘I can make a ghost come to me by calling it. Sometimes I’ll use an object - some personal effect or keepsake - as a focus; other times I just get the sense of the ghost by being close to it, and I can play the tune that makes it come. Then if I want to I can bind it and send it away.’

‘With music?’

‘Exactly. And I can do that with other things, too. Not just ghosts but . . .’ I hesitated. It was a big enough morsel to swallow already, without going into the full catalogue. ‘Let me tell you about Kenny,’ I suggested. ‘Maybe that’s the best way of explaining this.’

I started with the story of how me and Kenny had fought our one-sided duel on the roof of the tinworks, jumped forward to Kenny bleeding out in a car with my name on the windscreen, then went back and filled in as many of the gaps as Nicky’s brief orientation lecture and my own ferreting around the Salisbury would allow. I played down the demon-weavings, played up the wanting to find out what it was that Kenny had to tell me that was worth wasting a pint of his own blood to do it. From about two minutes in, I could tell from her expression that Nurse Ryall wasn’t buying it. Her frankly lovely face looked like a hod full of hard-core. And as soon as I’d finished, she shook her head.

‘If what you’re telling me is true,’ she said, ‘then why were you interested in the other man on the ward, too? The one with the puncture wounds.’

She had me there. By putting the emphasis so much on me and Kenny, I’d left out too much of the bigger picture - which maybe she needed to make sense of the other stuff.

I tried again, this time telling her about some of the stuff that was happening at the Salisbury - the epidemic of viol

ence, the weird graffiti, the tranced kid trying to jump off the walkway. But it made things worse, not better. There wasn’t any thread of logic connecting these things, and that became more and more obvious the more I talked about it. I was just whistling in the dark, trying to make a whole out of a bunch of parts that I didn’t even understand separately. I decided to finish what I’d started, but more from mule-headedness than from any feeling that it would do any good. By the time I got to Nicky’s stats, I could hear the hollow echo of my own words in the silent ward, and when I finally wound down Nurse Ryall didn’t make any answer at all.

But her expression was unhappy, and it was noticeable that she wasn’t telling me that I was a rabid dog who ought to be put down for the good of humanity. I waited her out, and at last she spoke.

‘Can you walk?’ she asked, very quietly.

‘Normally, I’m proficient,’ I said. ‘Tonight, I don’t know, but I’m prepared to give it a shot. What do you fancy? A movie? A Brick Lane curry?’

She didn’t seem to hear the lame joke. ‘Get your dressing gown on, then,’ she instructed me. ‘I’ve got something to show you.’

I threw the covers aside and swung my legs off the bed. Taking my weight on my hands, I touched down on the frigid tiles like Neil Armstrong making his one small step. But then Neil Armstrong was certified drug-free by NASA, and he was only contending with low gravity, whereas gravity seemed to be pulling me in a whole lot of random directions.

‘We haven’t got all night,’ Nurse Ryall said testily.

I stood up with barely a stagger, which I thought deserved at least a short round of applause. My paletot was in the bedside locker. I shrugged it on, to Nurse Ryall’s pained surprise.

‘You’re wearing that?’

‘It’s in right now,’ I muttered, concentrating on my vertical hold. ‘Rat-shit brown is the new black.’

She shook her head in disapproval, turned and strode off without a word towards the door. I followed her, assuming that she was leading the way rather than just giving up on me.

We went along a short corridor lit by fluorescent tubes that seemed agonisingly bright after the subdued lighting in the ward. There were backless benches along one wall where patients sat in some forlorn limbo, either waiting to be seen or just taking a breather somewhere on their personal roads to Calvary. Some of them looked hopefully at Nurse Ryall, as though they thought she might be their guide for the next stage of that journey: but not tonight.

We went out into the open air, across a courtyard where a few vans and a single ambulance were parked, and then back into a different part of the main building. It was darker and older here, and I started to recognise this or that turn in the corridor, this or that loitering spirit. We came to the main staircase: Nurse Ryall looked back once to see if I was following her, then went up. We were going to Kenny’s ward.

The cop on the landing - fortunately not the one I’d met two days ago - gave us a questioning glance as we approached the forbidden door. Nurse Ryall nodded to him, showed her ID and said nothing about me. She entered the code and pulled, but the door stuck for a moment as the lock’s old and cranky wards failed to pull back all the way. The cop took the edge of the jamb and added his own heft to hers: she thanked him politely.

I knew where we were going, but I didn’t know why, so I let Nurse Ryall keep the lead as we crossed the narrow space to the door of Kenny’s ward. There were still just the two beds occupied, Kenny and his roomie both asleep and breathing heavily. Nurse Ryall turned to me with an expectant look on her face.

I hesitated for a moment, glancing around the room. She said she’d show me something, but there was nothing to be seen.

‘What?’ I said.

She made an impatient gesture. ‘Listen.’

I did. Nothing but the rough-edged breathing of the two men that would have been snores if there’d been more strength in their chests to push them out. I was about to say ‘What?’ again, for lack of any better ideas, but then the two men stirred in their sleep and spoke.

It was just the usual half-formed mumble of a dreamer almost but not quite breaching the surface of consciousness. The kind of sound in which you can perceive the melted outlines of words without being able to separate them out or decode them. They ended in a subdued, lip-smacking swallow, a slightly tremulous sigh.

Both men. Together. The same sounds, in perfect synchrony.

13

I swore, very softly, and Nurse Ryall nodded.

But she’d asked me to listen before the men spoke, and now I realised why. I could see it as well as hear it: Kenny’s chest and the other man’s rising and falling in unison, their in-breaths and out-breaths coming at exactly the same time.

With a slight sense of unreality, I looked at the nurse and she looked back at me. There was a strained inquiry in her expression: What does this mean?

‘When did you notice?’ I asked her, ducking the issue just for the moment.

‘Two nights ago.’ Nurse Ryall’s voice was tight, unhappy. ‘You can listen to it for ages and not hear it. Then it just . . . hits you.’

‘Do you have any other patients in here from the Salisbury?’

‘From the what?’

‘From the same postcode. The Salisbury Estate in Walworth.’

She consulted her memory, shook her head doubtfully. ‘I don’t think so. I’d have to look in the admissions book.’

‘Is that up here or somewhere else?’

‘In the shift room. Listen, Mister - sorry, what was your real name again?’

‘Castor. Felix.’

‘What could make them do that? It’s not even possible!’

I crossed the room and picked up the black man’s chart. ‘Women living in the same house will synchronise their periods,’ I said. ‘Not right away, but after a while. Their bodies respond to each other’s hormones. Maybe this is like that - something autonomic that only kicks in after a while.’

‘That explains the breathing. It doesn’t explain the talking in their sleep.’

I looked up at her. ‘Do they do that a lot?’ I asked.

‘What’s a lot? They’ve done it before. Just like that, in chorus. But none of the other duty nurses has heard them do it. I know because I asked every last one of them.’

‘Anything you could make out?’

‘One word, sometimes. It sounds like “more” or “ma”. The rest is just gibberish.’

More? Ma?

‘Mark,’ I suggested.

Nurse Ryall nodded. ‘It could be that. Why?’

‘Because Kenny here -’ I pointed to the other bed ‘- had a stepson named Mark who died last year. Fell or jumped off a high building. And it hit Kenny hard - at least, according to some.’

Which explained nothing. I needed more than I had: needed a thread to follow through the maze, but Nurse Ryall had given me all she had. And she was well aware that I hadn’t returned the favour.

‘What is it?’ she demanded. ‘What is it really?’

‘Demonic possession,’ I said, deciding not to beat about the bush.

She gave a pained, incredulous laugh. ‘What, and you’d know?’

‘I’d know. I’ve seen it before.’

‘With two people? Two people at the same time -’ she groped for a phrase ‘- hooked up to each other like this?’

‘No,’ I admitted.

‘Well, then—’

‘Last time it was two hundred. The entire congregation of a church in West London. They all caught a dose of the same demon, and they all went out into the night to do unspeakable things to each other and to anyone else they met. I know about this shit, Charge Nurse Petra Ryall, because this shit is what I do for what I satirically call a living. They’re both possessed, and it’s one entity that’s possessing them. I don’t know what, and I don’t know why, but I might have a way of finding out. Is anyone else likely to come in here?’

She stared at me, her face a menagerie of misgivings. ‘At twe

lve. When the shift changes.’

‘Okay.’ I slid my hand into one of the paletot’s many inside pockets and took out my tin whistle. ‘Watch the door. If that cop makes a move, even if it’s just to scratch his arse, or if anyone else comes along, let me know. You’ll probably need to shake me or punch me in the shoulder or something. I may not hear you if you just whisper. Or even if you shout out.’

Nurse Ryall looked unconvinced, but she nodded.

I turned the chair beside Kenny’s bed to face me and sat down on it the wrong way round: there was no telling how long this would take, and if it dragged on it would be useful to have something to rest my elbows on.

Nurse Ryall watched me with uneasy fascination. ‘You’re going to do an exorcism?’ she asked.

‘I’m going to try,’ I said. Then I shut her out of my mind.

I started to play, random notes shaping themselves quickly into a sort of loose, aimless proto-tune. It was hard at first. It was only the lining of my lung that had been damaged, not the lung itself, but still the sharp pain whenever my chest muscles worked meant that everything cost me more effort than usual.

This part of the gig is like what bats and dolphins do: you throw out a sound and you wait for it to come back to you, subtly changed as it bounces off the world’s various bumps and hollows. And from those changes you work out what the place you’re in looks like: whether it’s high up or low down; what natural hazards there might be; what sort of company you’re keeping.

My death-sense rides the music as a wolf spider rides the wind, trailing a single thread of silk across a thousand miles of ocean. It doesn’t have any volition or direction - not at first - but the music takes it where it needs to go, and in return it shapes the music until the feedback loop that runs through my ears to my brain and on down to my fingers and my pumping lungs narrows and refines the formless feeling into something patterned, perfect, vivid - like hearing your own name softly spoken in a roomful of bellowed arguments.

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1