- Home

- Mike Carey

The Devil You Know Page 21

The Devil You Know Read online

Page 21

“You know what your sin is, Fix?” Nicky asked me, already tapping some terms into a nameless metasearch engine that displayed in black on dark gray. “The particular thing you’ll go to Hell for?”

“Self-abuse?” I hazarded.

“Blasphemy. The last days are coming, and He writes it in the Heavens and on the Earth. The rising of the dead is a sign—I’m a sign, but you don’t want to read me. You don’t even want to accept that there’s a point to all this. A plan. You treat the Book of Revelation as if it’s a book of police mug shots. That’s why God turns His face from you. That’s why you’ll burn, in the end.”

“Right, Nicky,” I said, already walking away. “I’ll burn, and you’ll tan. For so it is written. Call me if you get anything.”

I think I was in a fairly somber mood as I walked back along Hoe Street. Something about Nicky’s tirade had brought another recent memory to the surface of my mind—Asmodeus, telling me that I was going to miss the boat because I wasn’t asking the right questions.

Everyone’s a fucking critic.

Suddenly I was dragged out of my profitless thoughts. Passing a shop, I caught my own reflection in the window, at an odd angle, and someone else was moving behind me—someone I thought for a moment that I recognized. But when I turned, she was nowhere in sight. It had looked like Rosa—the girl at Damjohn’s club, Kissing the Pink, for whom Damjohn had sent because he thought I’d like to admire her backside. Pretty unlikely that she’d be here, I had to admit, but the impression had been a really strong one all the same.

Visiting Nicky is dangerous. You can catch paranoia as easily as you can catch a cold.

By the time I got back into Central London, it was the gloomy, smoky dog-end of the afternoon. Thus runs the day away. I tried Gabe McClennan’s office again, but this time even the street door was locked.

Well then, that encounter was postponed—but not canceled. And I was left full of a restless impatience that had me striding down Charing Cross Road as though there was actually somewhere I needed to be. If it had been a few months before, I would have taken a cab over to Castlebar Hill—to the Oriflamme, which for exorcists in London is home away from home. But the Oriflamme had burned down a while back when some cocky youngblood had tried to demonstrate tantric pain control in the main bar and had set fire to himself and the curtains. There was talk of reopening elsewhere, but for the time being, it was just talk.

So I retired to a pub just off Leicester Square that used to be the Moon Under Water and was now something else, where I downed a pint of 6X and a whisky chaser to fuel my righteous wrath. Nothing was adding up here—and a job that should have been textbook-simple was developing the sort of baroque twiddles that I’d come to loathe and mistrust.

The ghost was recent. She’d lived and died in a world that already had factories, cars, and wristwatches. Okay, in theory, that could still have placed her at the turn of the century, but that wasn’t the impression I’d got. The interior trim of that car had looked very modern and very luxurious, and watches with stainless-steel bands probably didn’t even exist before the 1940s. So she didn’t come into the archive with the Russian collection. And so the thing that tied her to the building in Churchway was something different—something I’d missed in the general rush to judgment.

Of course, I didn’t really need to know who she was or who she had been—not to do the job I was being paid for. All I needed was enough of a psychic snapshot to form the basis of a cantrip, and after last night’s adventures, I already had that. So why wasn’t I breaking out the méthode champenoise round at Pen’s instead of brooding in a loud bar in Soho?

Because I was being played for an idiot—and I never did learn to take to that.

If Gabe McClennan had been at the archive, this ghost had a history that I wasn’t being told about. And if someone was scampering around the building after hours, it seemed a fair bet that they were there to keep tabs on me. Either that, or it was somebody conducting some kind of business that they didn’t want daylight to look upon. I chased my thoughts around in decreasing circles for a while before getting back to the point—which I’d been avoiding pretty strenuously.

I’d told Peele that I’d do the exorcism by the end of the week. That gave me two more days, not counting today. But I had a strong enough fix on the ghost now to weave a cantrip anytime I wanted to. The job was effectively done. I could go in tomorrow, whistle a few bars, and walk away with the rest of that grand in my pocket.

And I’d be alive and in one piece and able to do this only because the ghost had stepped in to stop me before I made that fatal misstep in the dark.

There’s a good reason why I don’t think too much about the after-life, and it’s not squeamishness. Or at least, it’s not the kind of squeamishness that would make you swerve aside from thinking about your brakes failing when you’re driving down a one-in-three cliff road—or shut off thoughts of sharks when you’re bathing in the sea off Bondi Beach.

It’s my job. Can I put it any simpler than that? It’s what I do. I send ghosts on to whatever comes next. Which means that if there’s a Heaven, say, then I’m doing a good thing, because I’m opening the door to their eternal reward. And on the other hand, if there’s no world after this one—nothing at all aside from the life we know—then I’m just erasing them. I’ve always had my own way of getting around the problem, which is by refusing to think of the ghosts themselves as human. If they’re just psychic recordings—the residues of strong emotions, left on play-and-repeat in the places where they were first experienced—then where’s the harm?

Now I could feel that particular defence crumbling and water leaking through more holes than I had fingers to plug them with.

I nursed the whisky for half an hour, then ordered another and brooded on that. And I was about to order a third when a glass appeared in front of me. It was black sambuca, and it had been served in that showy way that normally annoys the hell out of me—set on fire, with a coffee bean floating on the top—but when the woman eased herself in on the stool next to mine and leaned forward to blow out the flames, I forgot all about that.

The phrase “drop-dead gorgeous” is overused, in my opinion. Did you ever seriously look at a woman and think that your heart would stop? That the sheer intensity of her beauty threatened to burn a hole through your skull so that your brains would bleed out?

I was looking at her now.

She was tall and statuesque, where normally I go for petite and cute, but you could tell at one glance that she was the sort of woman that categories would crash and founder on. Her hair was a coal black waterfall, and her eyes were of a matching color, so intensely dark that they seemed to be all pupil. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, then her soul had an event horizon. She would have looked good with a Lady d’Arbanville snow-white pallor—good but Gothic. She was every shade in white’s spectrum, which I’d never appreciated before. Her skin was the palest ivory, her lips a darker and richer color, like churned cream. The black shirt she wore seemed to be made of many layers of some almost-sheer material, so that as she moved, it offered microsecond glimpses of the flesh beneath. By contrast, her black leather trousers showed nothing but surface contours and talked to me entirely in terms of textures. A silver chain, entirely plain, decorated her left ankle, which was crossed over her right. Black stilettos sheathed her feet.

But it was her smell that was having the strongest effect on me. For a moment, when she first sat down, it had hit me as a hot wave of rankness like the stink of a henhouse after a fox has been busy in there. Then a second later I realized I was wrong, because the smell had opened up into a thousand shades of meaning: subtle harmonies of musk and cinnamon and dew-wet summer air overlaid on sweet rose; heavy, seductive lily; and undisguised human sweat. There was even a hint of chocolate in there, and those hot, sticky boiled sweets called aniseed twists. The total effect was indescribable—the smell of a woman in heat lying in a pleasure garden that you had visited a

s a child.

Then those astonishing eyes blinked, slowly and languorously, and I realized that my appraisal had taken several seconds—seconds in which I had just been staring at her with my mouth slightly open.

“You had a certain look about you,” she said, as if to explain the free drink and her presence. Her voice was a deep and husky contralto; the equivalent in sound of her face. “Like a man who was reliving the past—and not really getting a lot out of it.”

I managed a shrug and then raised the sambuca in a salute. “You’re good,” I admitted, and took a long sip. The rim of the glass was still hot, and it burned into my lower lip. Good. That gave me some point of contact with reality.

“Good?” she repeated, seeming to give that a moment’s thought. “No, I’m not. Not really. You can take that as a warning.”

She’d brought her own drink over with her, too—something in a tall glass and bright red that could have been a Bloody Mary or plain tomato juice. She clinked glasses with me now and drank off half of it in one gulp.

“Given how short life is likely to be,” she said, setting the glass down and favoring me with another high-octane stare, “and how full of pain and loss and uncertainty, it’s my opinion that a man should live for the moment.”

If this was a chat-up line, it was a new one on me. I took another mouthful of her smell; I was disconcerted to find that I had an erection.

I groped for a bantering tone. “Yeah, well, normally I do. Most of the moments I’ve had today haven’t been up to all that much.”

She smiled. “But now I’m here.”

Her name was Juliet. More than that she wasn’t interested in telling me, except that it came out that she wasn’t from London. I could have told that from her accent; or rather—as with Lucasz Damjohn—her lack of one. She spoke with a kind of diamond-edged clarity, as though she was setting syllables down next to one another in line with a pattern she’d already memorized. It might have made her sound like a Eurovision Song Contest presenter, but when did Eurovision ever make you stand inside your pants?

She wasn’t interested in finding out about me, either, which was great. The less I talked shop right then, the more I liked it. Whatever the hell we did talk about, I don’t remember it now. All I remember was the absolute certainty that we were going to walk out of that bar and find somewhere where we could fuck like demented rabbits.

In the meantime, another glass of black booze arrived, and then another, and another. I drank them all without tasting them. Everything seemed to be black when you looked at it properly; Juliet’s eyes were black kaleidoscopes that stole the world away from you and then gave it back again translated into subtle, midnight shades.

We tumbled out of the bar into the black night, lit by the thinnest sliver of moon, and then into a black cab that drove away without needing to be told where we were going. Or maybe I did mention a destination, some part of my brain still trying to deal with the mundane realities while I groped at Juliet’s shadowy curves and she fended me off without effort.

“Not here, lover,” she whispered. “Take me somewhere no one can see.”

Then the cab was receding into the distance, and we were standing on the pavement outside Pen’s house. The windows all black except for one; Pen was in the basement, and I remembered vaguely that I hadn’t seen her for two days. It didn’t seem important right then; nothing was important except getting into my room with Juliet and locking the door. Once that was done, the whole damn world could end, and I wouldn’t care.

I couldn’t get the key into the lock. Juliet spoke a word, and the door sprang open of its own accord. What a useful trick! She was leading me by the hand up the stairs, and there was a bubble of perfect silence around us, so that when I spoke her name in a drunken slur, I couldn’t even hear it myself. She looked around at me and smiled, a smile full of almost unbearable promise.

My own door opened just as easily as the street door. She drew me inside and closed it behind us. “Oh Jesus, you’re so—” I blurted, but she shushed me with a finger on my lips. This wasn’t the sort of occasion where you had to flatter and cozen your partner with clumsy words that didn’t even fit. Her blouse fell away without her touching it; so did her trousers and her shoes. Her flesh was uniformly pale, a dazzling contrast to her dark hair and eyes. Even her nipples, and the area around them, were all as pure and perfectly white as if they were carved from bone. Naked except for the slender chain tinkling out its seductive, silvery tune on her ankle, she pressed me to her, and her lips sought mine, one strong hand on the back of my neck, holding me in place.

“Now,” she growled. “Give it to me. All of it.”

She was tearing at my clothes with her other hand, and it didn’t surprise or alarm me that her long nails shredded cloth like paper, making deep lacerations in my flesh along the way. She fumbled briefly between my thighs, until with her help, I tore free of what was left of my trousers and pants. Our mouths fused, then our groins. We merged at last, Juliet holding the contact as she drew the breath from my lungs into hers, and heat expanded from my heart and crotch to fill the world.

I thought it was true love. But then the heat grew more intense, went in an instant from blood-warm to blistering, and, opening my eyes, I saw that the two of us were wreathed in red fire that hid the room from my sight.

Twelve

I WAS IN AGONY. THE TERRIBLE HEAT WAS RUNNING through the rooms of my body like a monster too big to be contained in me, searching for doors and windows by which it could escape, looking to be joined with the greater heat that enveloped me. I tried to pull back from it, but it was as though I was welded into place: crucified on some twisted tree that wound around and around me and held me tight. I couldn’t even scream; my mouth was already open, but something was locked onto it, stifling me so that I couldn’t make a sound as I was devoured.

There are two ways in which pain can take you. Most times, if it’s bad enough, it will just throw your wits out of the window. But if you’re panicking already, then pain can be an anchor to cling to—something you can use to get yourself focused again. That’s how it was with me. The agony of the fire shrilled through me like an alarm bell, waking me out of the trance that the succubus had lulled me into.

That’s what she had to be, of course. Her black-on-black eyes and her natural perfume should have warned me, but I was inside her orbit before I knew what I was dealing with. After that, I was thinking only with my dick and no more capable of rationalizing what was happening to me than I was of dancing the cancan with my legs sewn together.

So I was going to die. And it was going to hurt.

Succubi consume your soul, and they take their time because—well, putting it as delicately as I can, because the orifice that they use for the job doesn’t have any teeth. I could already feel myself weakening, sliding away, and the hell of it was that the feeling was one of febrile, throbbing pleasure. She was killing me, and she was making me enjoy it.

But at least I was thinking again, thinking through the pain and the arousal, like trying to tune into my own voice on a radio through wave after wave of howling static. And because I was thinking, I saw that I had a chance—an outside chance, somewhere between slim and snowball-in-Hell.

My mind was saturated with the succubus’s subliminal scream of love, with the intoxicating, stupefying presence of her, expressed in smell and taste and texture, all urging me onward and inward. That was how she worked.

And as an exorcist, I could use that presence, that vivid, perfect sense of her. That was how I worked.

With my hands free and my whistle to my lips, it would have been easy. Well, it would have been three or four degrees farther away from impossible. With my whistle somewhere on the floor in the shredded remnants of my coat and my mouth locked tight against hers, I had to improvise.

I reached out with my left hand, flailed blindly for a moment, and then found a hard surface: the slatted cover of the rolltop desk. The pain was excruciating, and so

was the pleasure, but I did my best to ignore them both. I started to tap out a rhythm.

It wasn’t a full cantrip, but it was the start of one. When I play the pipe, I use pitch and tempo and slur and every damn thing else to turn the endless involutions of what I’m seeing in my mind into something ephemeral floating in the air in front of me. Compared to that, what I was doing now was like trying to make a functioning revolver out of prechewed wood pulp, and then aim and fire it. All I had was the one ingredient to cook with, the one dimension to work in.

It was never going to dispel the succubus, but I was hoping it would throw her a curveball. It did. A tremor went through her as the rhythm built and hit, and then for a moment or two she froze, some of the terrible strength going out of her sinuous limbs. I used those moments to push my head back, against the pressure of her cupped hand, and get my mouth away from hers.

I gulped in a lungful of air. By contrast with the searing heat that raged through me, it felt like swallowing a bucket full of ice splinters. No time to dwell on the agony, no time to go for a second, deeper breath. Instead I started to whistle, in quick but halting counterpoint to the rhythm I was still beating out with my fingers.

The effect on Juliet was spectacular. Her implausibly perfect face convulsed, her features seeming for a blurred instant to melt and run into some other configuration. She screamed in rage, and it was such a terrible sound that I almost lost the tune. Her grip tightened on me, threatening to crush my chest, but only for a moment. The shrill staccato of the cantrip bit into her, and she let me go, staggering back against the wall.

As Juliet went down in a fetal crouch, I crashed to my knees on the floor. The impact jarred me enough to make the breath hiccup out of me, and although it was only for a moment, the succubus drew strength enough from the brief stammer of silence to recover and straighten up again. I caught the tune at the head of the next bar and quickened the rhythm. She froze in place again, glaring down at me.

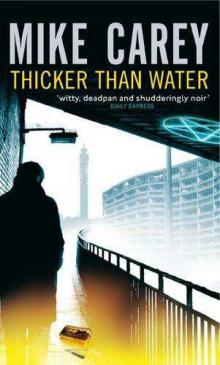

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1