- Home

- Mike Carey

The City of Silk and Steel Page 12

The City of Silk and Steel Read online

Page 12

The Second Librarian would brush him off in an embarrassed fashion, breaking out of his embrace with a cough and a muttered, ‘Yes, yes, of course, father. Don’t fuss so.’ His behaviour did not alter in the least. He continued, reckless and unrepentant as ever, in spite of the First Librarian’s fears. Rem watched these repeated scenes between father and son with disapproval and apprehension. As the Ascetics’ violence escalated, the number of people frequenting Bessa’s drinking houses and gambling halls was falling rapidly, and men like Warid were starting to stand out. Her more pointed warnings were met with a similar rebuttal.

‘Oh calm down,’ he would say. ‘Can’t put everything on hold for a few hooligans. Stop nagging. I’m not afraid of them.’

The Second Librarian was not afraid for himself, but he had cause to be. Nor was he the only one at risk. Rem now insisted that he came into the library through the side entrance rather than the main doors, and took to hiding him more carefully when he was passed out drunk, far from the eyes of any scholars who might happen to be passing. The library had become the eye of some inconceivable storm, and she clung to it even harder than before, stalking its corridors and guarding the fragile equilibrium of its peace with a ferocious intensity.

And then one evening the storm rolled over her, as she had always known it would.

Rem was sitting outside on the library’s imposing marble steps like a sentry on duty, soaking up the last vestiges of heat from the stone. Inside, the First and Second Librarians were asleep. It was long past closing time, and she should have woken them hours ago so that they could go home. But instead she had left the Second Librarian where he lay on the floor, and let his father doze off in front of his desk, his evening cup of hibiscus tea untouched at his side.

She sat gazing at the stars with an expression of intense concentration such as is often worn by people lost in thought, so that afterwards an observer, had anyone been around to see, would have said that she seemed to be watching for the faint plume of smoke that curled in an elegant cursive towards the darkening bowl of the sky. As it was, the only sign she gave of having noticed the fire at all was a slight stiffening in her posture, perhaps merely a reaction to the growing cold.

After a few minutes, she rose from where she had been sitting and walked deliberately over to the well in the square in front of her, where a few women had gathered to draw water for the evening.

‘Look at that smoke,’ she said as she approached them, pointing in the direction of the plume. The women glanced up with worried faces. ‘Must be another attack,’ one said quietly. ‘That’s the fifth this week!’

‘It could easily catch, especially in this dry weather,’ Rem said. ‘I’m going to see what I can do to help.’ A couple of the women went with her, while others ran to fetch husbands and neighbours. As they hurried through the city, they were joined by more and more people, flocking towards the source of the smoke. Some carried jugs of water, running with care to avoid spilling any.

Rem began to see confusion on the faces around her: the smoke was coming from the outskirts of Bessa, not the pleasure district. The western edge of the city was a respectable residential area, a neighbourhood of lower-order dignitaries and the better class of merchant. The frightened murmuring of the crowd increased.

‘They’re targeting people’s homes now?’

‘But this is a good area. What could they want with anyone here?’

‘Oh, we all know that,’ a large woman dressed in orange interrupted loudly. ‘We all know what they’re doing here.’ She glanced around to make sure that she had people’s interest, but did not continue, only raising her eyebrows significantly.

The street was becoming thick with smoke, forcing many to turn back, coughing and choking. With the fire this far advanced, there would not be much left to save.

Rem pressed onwards, following the white tendrils which threaded with lazy menace around her feet, as if to trip her. Speculation was growing in the crowd. Whose house could it be? Were they at home when the fire started? Were they still alive?

For her own part, Rem already knew the answers to these questions. She had seen this fire in her mind’s eye long before she noticed the smoke in the sky. The houses around her were already starting to look familiar, resolving into forms which she passed frequently enough that their new shroud of smoke rendered them uncanny, like the faces of friends seen under water.

She rounded the last corner to see the First Librarian’s house ablaze, flames leering from its windows. A circle of people had gathered at a safe distance, shielding their eyes and monitoring the progress of the fire. No one wanted their own house to catch a stray spark. Rem could hear Warid’s name being muttered, in tones ranging from pity to malicious satisfaction. The orange woman nudged her arm.

‘I only pity his poor father,’ she said. ‘That reprobate son of his knew what he was letting himself in for, but what did his father do to deserve it? The poor old man had no idea. Where is he going to go now? It’s a mercy they weren’t at home – no question where the son is, that drunken lecher. Now I’m not saying he deserved it, but . . .’

The woman carried on speaking, but Rem no longer heard her. She was staring at the burning house, the mesmerising flicker of the flames, but her gaze passed through it, penetrating the crumbling walls to scrutinise their past, and the hearts and minds of those who had burned them. She winced as the full horror of what she was seeing came clear to her.

‘They didn’t come for Warid,’ she whispered. Then, louder, cutting the woman beside her off in mid-squawk. ‘You’re wrong. You’re all wrong. They didn’t come for Warid. They came for his father. They came for the First Librarian.’

The people around Rem stared at her as if she was mad, but she didn’t notice. She was running over all she knew about the Ascetics in her head, hoping desperately that she was wrong. They scorned the pleasures of the world. They worshipped a single truth, against which all other truths were counted deceit, and what they counted deceit, they burned. No, she wasn’t wrong. In fact, she had been a fool not to see it before.

By this point she had turned away from the burning house, was already shoving through the crowd, running back the way she had come. She had thought the Ascetics would target Warid, had even expected them to, but she had been mistaken. They had come for his father. His father, the head of the library, the archivist of ten thousand different truths, all clamouring at once. The library in Bessa was a paradise: it had more voices within its walls than the Jidur. But as she ran home, Rem could see it for the first time as it must appear to Hakkim: a desert of dry parchment, filled with nihareem.

Her first priority, obviously, was to save the scrolls. How exactly this was to be done was a difficult question. Back in the library, Rem fought tears as she gazed at the crowded shelves, knowing beyond certainty that she must empty them, and as quickly as possible.

There was no point in going to the sultan for protection. Al-Bokhari was as worried as anyone by the Ascetics’ violence, but the strength of his armed guard was focused on keeping peace in the streets and maintaining the security of his palace. Besides, he was too concerned about his own position to spare much thought for the health of civic institutions. In the Jidur, Hakkim’s speeches had taken a turn deeply disquieting to Bessa’s ruler. His general condemnation of excess and pleasure was becoming more pointed and personal in import, containing dark references to a certain great man’s fondness for drink, his wild feasting, his revelries which lasted for days on end. He had recently delivered an attack on the evils of Bessa’s brothels in which he singled out for special mention Al-Bokhari’s own seraglio, with its decadent cohort of three hundred and sixty-five concubines.

All this was bordering on the treasonous, but Hakkim’s invective was unsurprisingly popular with poor shopkeepers and artisans. Al-Bokhari had many faults, not least the free sway he gave to his appetites, but he was no fool, and he knew full well that the last thing the Ascetic cause needed was martyrs. So Ha

kkim and his followers were left, for the time being, to continue their activities largely unhindered.

And so was Rem.

She had decided from the start that it would be better not to confide her decision to the First and Second Librarians. Though they were unlikely to oppose her, the prospect that they might provide useful support for her efforts was still more remote.

The chances of them discovering her actions unaided, moreover, verged on impossibility. The First Librarian had taken the loss of his house badly. Most of his dead wife’s possessions had been inside when it burned down, reduced to ash along with his clothes and a large portion of his savings. Rem had made up a bed for him in his office, and now he rarely ventured outside. The Second Librarian mooched around as he had always done, but drank less frequently and with greater secrecy. He guiltily avoided his father’s presence and, Rem noted, made a conscious effort to stay sober when making enquiries about renting a new house. She had taken to spreading a blanket over him when she found him sleeping between the shelves, feeling both resentful and strangely tender towards these new inhabitants of the city once reserved for her alone. The First and Second Librarians weren’t much of a family, but Rem felt protective towards them all the same.

The library had turned into a sort of crisis centre, filled with the dispossessed and afraid, and it was under her care. During the still nights, hearing the other Librarians’ distant snores and feeling the comforting presence of the scrolls around her, nestling like ancient birds in the darkness, it was easy for Rem to slip back into the sense of peace she had felt in earlier days, to forget the terrible warning that the sight of the burning house had awakened in her mind. But her visions were filled with burning scrolls and crumbling masonry: she knew beyond a doubt that the library was no longer the sanctuary it appeared, and none of those who sheltered within it could do so for long.

It was not difficult for Rem to borrow the key to the Rare Texts Room again from the First Librarian, and even easier to get a copy cut in the market for her personal use. Although their existence was not put about widely in Bessa, for fear of unwelcome attention, some of the scrolls in this room were of great value, if one knew where to sell them. After a decade of service, Rem knew. She also knew that these would be the easiest ones to rehouse, the ones that were coveted by the world at large for their beautiful illustrations and exquisitely illuminated characters, their wooden rollers inlaid with jewels and their gold leaf. It was the others, the hundreds of thousands of plain scrolls written on simple parchment, that would present the challenge. They had no market. No one, aside from herself and a few penniless scholars, had any interest in them at all.

It was here that Rem moved into the next phase of what she privately termed her evacuation plan. Selling the contents of the Rare Texts Room raised less money than she had hoped, but still enough for the purchase of a disused bakery in Bessa’s merchant district. Its previous owner no doubt felt that he had thoroughly cheated her, could not believe his luck when his eccentric buyer seemed unconcerned at the sight of the rotting door hanging from its hinges, picked her way through the piles of rubbish and dead rats inside without comment, and smiled with satisfaction as she pronounced the place perfect.

She had found what she wanted as soon as she entered the room, gleaming dimly in the far corner: the heavy metal ring of a trapdoor. Bakers in desert cities like Bessa had a simple method for stopping their produce from spoiling. They built their storerooms underground, where the air was cooler. Coincidentally, this also made them ideal for storing scrolls, the lower temperatures protecting the parchment from heat damage, degeneration and the risk of fire.

Rem cleaned out the traces of mouldy bread and flour from the cavernous room, and moved a steady stream of scrolls into it over the course of the next month. If either of the other Librarians noticed the slowly emptying shelves in the library, they did not think it important enough to comment on.

When she had filled the storeroom almost to its ceiling, she began the long-term loans. This was not an easy decision to make; putting the scrolls in hiding was one thing, but sending them into exile, into other peoples’ homes, where she would in all probability never see them again, hurt Rem deeply. But Hakkim had started burning the sacred texts of other preachers in the Jidur, and it was a mark of the fear he commanded that none of them had tried to stop him, or even protested. If the threat he posed to the library had seemed at all distant or unreal to Rem before, it was ever-present now.

So she steeled herself, and decided to work by section, starting with the scientific and medical treatises. This area always had a steady trickle of visitors, mostly student apprentices working for Bessa’s doctors, surgeons and apothecaries. The library was large, however, and it was never difficult to find a reader who was standing alone, or at least far enough from the next person that there was no risk of their conversation being overheard. Once she had spotted a potential candidate, Rem would wander to their side and cough politely, waiting until they looked up from the scroll in their hands.

‘Are you finding it interesting?’ she would ask softly, ‘Do its ideas please you? Then take it home with you. Read it, share it with your friends. All I ask is that you keep it safe.’

A huge advantage of dealing with scholars is that they are not stupid. They had all been to the Jidur on occasion, had all heard Hakkim speak, and they understood what she wanted almost immediately. Most accepted a scroll without question. Some even offered to take a few more. No one asked why: the only really surprising thing to those who had paused to think about it was that the Ascetics had not attacked the library already. Many were confused when Rem waved away their offers to return the scrolls after the trouble had died down. It seemed only logical to them that it would die down, that Hakkim’s hold on Bessa would be broken any day now, that Al-Bokhari would move against him, and the Ascetics would dissipate, as if they had never been. After all, the violence had been escalating for months: surely someone would do something about it soon?

That each day which passed without change signalled more clearly than the last that no one would do anything did not seem to have occurred to them. But the people of Bessa could not be blamed for their lack of foresight. The city was hiding its eyes behind its hands like a little child, waiting to be told that everything was all right now, that it was safe to look, that the worst was over. One peek and the city would dissolve into abject terror; a lack of clear vision was the only thing keeping it going. By the very nature of her gift, Rem did not have that luxury.

It was a slow process, but gradually the library was emptying out. Considerable sections of the shelves were empty now, like patches on an ornate rug worn through to the bare weave. Yet there were still thousands of scrolls left: the library was vast, and Rem knew that it would take more than the scattered efforts of some well-meaning scholars to save it all.

She increased her efforts nonetheless, trawling the corridors ceaselessly for likely-looking candidates. Soon she was speaking to everyone she came across, even if they seemed uninterested or slow-witted. She abandoned her efforts with the medical texts when there were so few of them left that students no longer came to the library to read them, and moved on to the poetry scrolls.

It was here that she met Nabeeb. She came across him by chance one day when she was patrolling the long avenues of shelves. He was a slight man, dressed in black, though in a different style to the Ascetics. Where they wore thick cloaks, his garments were less voluminous: a simple black shirt and a pair of trousers. Looking at him carefully, Rem realised that he was a regular visitor to the library. She had seen him many times before, wandering between the rows of texts with a measured pace and an earnest expression. She came closer to him and looked at the scroll he was reading. He glanced at her with mild grey eyes.

‘Can I help you?’ he asked.

‘You come here quite often,’ Rem replied. ‘You must find many things that you like. I am Rem, the Third Librarian here, and I would be honoured if you wo

uld take some of these scrolls away with you, that you may read them at your leisure. I only ask that you keep them safe.’

The man put his head on one side, appeared to be considering.

‘I’m Nabeeb,’ he said. ‘I know what you’re asking. I’ve seen you talking to others before. It won’t work, you know.’

‘What?’ Rem was startled into abruptness, and there was an edge to her voice.

‘I only meant,’ he answered, holding up a hand in placation, ‘that it will take you a very long time. Individuals, a few scrolls at a time. It’s no way to clear a library this size.’

Rem leaned closer to him, her eyes brightening with interest. ‘Do you have a better idea?’

‘Corpses,’ he answered promptly, and then, in a shy rush, ‘I am an undertaker by trade. All corpses must be buried outside the city’s walls. So, I prepare them for burial, then drive them outside Bessa’s gates. The funerals themselves take place within city limits: when I actually bury the bodies, I am alone. I never get any trouble, from the palace guard or the Ascetics. People are put off by the idea of searching a hearse – it seems disrespectful. So if I were to carry some scrolls out with me the next time I make a burial trip, I could get them outside the city in complete safety. We could wrap them in winding sheets, and no one would ever think to check them.’

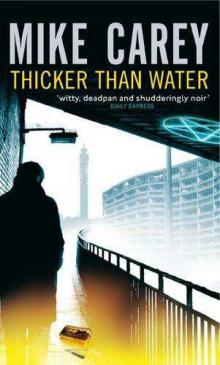

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1