- Home

- Mike Carey

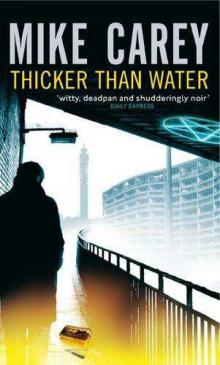

Thicker Than Water Page 10

Thicker Than Water Read online

Page 10

Juliet finished her glass in a single swig and licked her lips. There’s something subversive about the way she does that: it makes you think of huge jungle cats tonguing gobbets of bloody tissue from between their teeth after a kill. Nicky looked away - not out of fear or distaste but because the bottle had cost him three hundred quid and he knew that she hadn’t really tasted it going down. Juliet is only an epicure when it comes to flesh: anything else she sees as window dressing.

‘So you did it,’ I observed, clinking glasses with him. ‘Congratulations.’

‘Thanks.’ He took another snort of the Pauillac’s heady bouquet. ‘I thought I might go for a double bill next time.’

‘Yeah? What movies?’

‘Night of the Hunter and They Saved Hitler’s Brain.’

I blinked. ‘I don’t see the connection, Nicky.’

‘Stanley Cortez cinematography. The Salisbury is a fucking dump, Castor.’

The change of topic threw me for a moment. ‘Yeah,’ I agreed. ‘It’s high up on my list of places not to go. But it was meant to be a model community, right? The estate of the future.’

Nicky nodded. ‘That was the hype,’ he said. ‘They got Derek Winch in to consult, back when everyone still thought he was God. Some other guy built it, though - don’t remember the name, but you can see the thinking. Get Winch’s name on the project, then ship someone else in to do it for half the money in a quarter of the time. They were gonna have shops, restaurants, cinemas up there, fuck knows what. The idea was that you never had to touch the ground if you didn’t want to - you could live your whole life up in the towers. Use the walkways like streets, come and go as you pleased, be one step closer to Heaven. Which, coincidentally, was the slogan they used when they opened it up for applications.’

‘Heaven,’ Juliet echoed, pouring herself another brimming glass. Her tone was heavy with sarcasm.

Nicky watched her tilt and swallow, with a slightly tragic face.

‘But it all came apart,’ I prompted him.

He nodded. ‘Before they’d even finished building it. The usual bullshit. They went in without enough money, cut corners, raced deadlines to save political face. But some people will tell you the design was screwed to start with.’

‘How do you mean?’ I asked him, listening with half an ear because I was still thinking about the teardrop graffiti with its corona of radiating lines. Actually I was thinking about that and Gwillam, and I was almost making a connection, but chasing it just made it flicker and fizzle out before I could grab hold of it.

‘The walkways were the main problem,’ said Nicky. ‘Having streets eighty feet off the ground seemed like a fantastic idea when they started out. Pure sci-fi. They were talking about a city in the air - linked estates from Peckham to Elephant and Castle. Leave your worries on the ground, take to the skies and live clean.

‘Only it turned out that you left a lot of other stuff on the ground, too. Like law and order. The Salisbury was a vertical maze - and it was impossible to police the place because muggers, pushers and gang-bangers could be somewhere else before the cops ever got within spitting distance. The walkways turned into thieves’ rookeries. And then people started dumping their shit out on them rather than carting it down to the ground floor. And then the damp set in because the concrete was made out of spit and bumfluff. Closer to Heaven, maybe, but you bring the weather with you.’

I took a fastidious sip of the wine: Juliet was emptying the rest of the bottle into her glass, so I figured I’d better make it last. ‘That’s more or less what I heard,’ I said. ‘Didn’t Blair do a photo op there back in ’97, just after he got in?’

‘Shit, yeah. That’s where he did his “forgotten people” speech.’

‘And then—?’

Nicky sneered nastily. ‘He forgot them.’

I decided I’d talked shop for long enough. We were here to celebrate, and we weren’t making much of a fist of it. I toasted the echoing vault around us and the newly painted screen at the far end of it. ‘To the Walthamstow Gaumont,’ I said. ‘Like its owner - come back from the dead with grace and style.’

Juliet drained her glass and crushed it in her hand, letting the fragments spill out between her fingers and squeezing out a few drops of blood to follow them.

‘Ye’air gva aku norim, hesh te va’azor,’ she said.

Nicky gave her a pained stare. ‘Which is . . . ?’

‘The closest thing I know to a blessing.’

‘Well, thank you.’

‘You’re welcome.’

‘And now I’ve got succubus blood on my carpet. Is it - like - acid or something?’

‘It’s like blood,’ said Juliet. And then to me, ‘Would you like a lift?’

‘Where are you going?’ I asked her.

‘Home. To Susan. Our working hours haven’t overlapped for the last three days. I’m starting to forget what she tastes like.’

‘Then it’s thanks but no thanks,’ I said, resisting the urge to ask for further details that I probably didn’t need to know. ‘I’m going back into town.’

‘To this council estate?’

I shook my head. ‘To Whitechapel. The Royal London.’

‘The hospital? Why?’

‘That’s where they took Kenny Seddon.’

‘Your enemy?’

I laughed at that. ‘Not my enemy, Jules. Not exactly. Nor my friend, ever, that I knew of.’

‘You said you fought over a woman—’

‘A girl.’

‘—Who you both lusted after. Didn’t that make you enemies?’

‘I never lusted after Anita Yeats.’

Juliet looked me in the eyes for a long moment. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘You did. At some point.’

There’s no point arguing with Juliet about something like that. ‘Well, I never did anything about it,’ I amended.

‘Leaving that aside,’ Nicky interjected, ‘isn’t this same shitbird Seddon in a coma or something?’

‘Yeah. He is.’

‘So, what - you want to leave some fucking flowers?’

‘No. I just thought it wouldn’t do any harm to take a look at him - and if I get the chance, maybe try a laying-on of hands. You know I can sometimes do the psychic wiretap thing.’

Juliet shook her head. ‘This is how you approach all your cases, Castor. You wander around the edges of them until things happen to you. That’s not a plan - it’s the absence of a plan.’

‘What would you suggest?’

‘In this instance, I’d go and find Gwillam and threaten to sink my teeth into his throat if he didn’t tell me what I wanted to know.’

‘But I don’t think he knows what I want to know,’ I pointed out.

‘Then you’d have the pleasure of ripping his throat out. And incidentally - notwithstanding my earlier point about not asking me for any favours - if your path and his do cross again, I want to be there. He bound me the last time we met: bound me and humiliated me. It would be pleasant to balance the books.’

Job satisfaction. It’s a very important part of what we do.

‘So that would count as a small favour from me to you,’ I mused.

‘Hypothetically, I suppose. It hasn’t happened yet.’

‘But in the futures market it’s solid gold. Can I borrow on it?’

Juliet chastised me with narrowed eyes, but she didn’t say no.

‘I’d be really grateful for a second opinion,’ I said. ‘Whatever it was that I was sensing down there on the Salisbury, it wasn’t your bog-standard haunting.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Because it didn’t feel right. It’s too big, and it doesn’t have a proper focus. It’s like someone tore a whole bunch of ghosts into confetti and sprinkled them over the entire estate.’ I threw out my hands in an inadequate gesture, fingers spread. ‘The feeling is everywhere, Juliet. I’ve never come across anything quite like it.’

‘Couldn’t it just be a lot of different ghosts?

You said yourself this place is a slum. And it’s old enough now for a lot of people to have died there.’

Reflexively, I touched my left hand to my chest - to where my tin whistle nestled close to my heart. ‘No,’ I said. ‘It couldn’t be that. I’d hear it differently. You know how my thing works. To me, a bunch of ghosts in the same space would be kind of like half a dozen bands jamming in the same room. This was just one impression. One thing, but spread out over a wide area. It’s like - you know how they say ants and bees don’t have individual minds? That they’re part of a hive mind, a collective self?’

‘Go on.’

‘That’s all. It was all around me, and it was all the same thing. Big. Broken up. Not localised. Equally strong over the whole area of the estate, which is like a quarter of a mile from end to end. Did you ever come across anything like that?’

Juliet considered this, furrows of concentration appearing on her brow. While she thought, I put some time into just admiring her face: it never felt like time wasted.

‘Possibly,’ she said at last. ‘But not for a long time.’

‘Will you go take a look?’

She didn’t answer for a moment. She was looking at me as if she was trying to read something in my face. Or maybe she was just exasperated by my inadequate verbal photofit.

‘If I’m passing,’ she allowed, ‘I’ll take a look.’

‘Thanks, Juliet.’

‘If I’m passing, Castor. You wait patiently and you don’t hassle me. I’ll call you as and when.’

‘Thanks,’ I said again.

That would have to do, for now. I thanked her for the advice about jugulars and hit the road.

6

I hadn’t thought about Anita in years, and now suddenly I couldn’t get her out of my head. Every time my mind went into idle, as it did while I was Tube-hopping south and west across London, old memories of her kept popping up out of nowhere - no doubt shaken and stirred from the cerebral substrate by the pants-wetting trauma of seeing my name written in Kenny Seddon’s blood.

Had I fancied her? Jesus, who was I trying to kid? Of course I had. More than once, in fact. The first time had been when I was four and was dragged against my will to Northcote Road Primary School to see my brother Matt playing Joseph in the nativity play. Anita was his Mary, and I liked the way she smiled. She delivered her lines nicely, too. I committed two of them to memory, and used to repeat them to myself every once in a while for the sheer pleasure of the sounds: “Come, Joseph. I am close to my time and we must reach Bethlehem before our baby is born” and “I thank you for your gifts and for your great kindness.”

But that was just a childhood infatuation. The year after she stabbed Kenny - the year she turned sixteen - Anita was the most beautiful thing that had ever walked on two legs. And she’d saved my life! So naturally I was besotted with her to the point of insomnia, and used her as the raw material for a thousand fantasies ranging from the sloppily romantic to the baldly pornographic.

It didn’t help, though. She’d completed her metamorphosis by that time: she was all grown up and I was a kid. The yawning chasm of two years was way too wide to vault across - at least in that direction: if I’d been older than her it would have been a different story. She dated one of the boys who loaded the vans at Hannah’s pie bakery in Arthur Street: a guy named Alan, who was eighteen and had all the advantages of a job, a car and a total absence of acne. I hated him and wished harm on him, even though he’d once given me a quid to put a bet on for him at Coral’s.

But that passed. It always does. You learn to scale your desire to things within your scope, when you’re fourteen. Or at least you learn to distinguish between desires you can hope to satisfy and ones that are just between yourself, your conscience, and the box of tissues on your bedside table.

By the time I finally lost my virginity - to Carole Aubrey in the car park of the Red Pepper Club on Rice Lane - I wasn’t even fantasising about Anita on a regular basis. The top slots were filled with movie actresses and female vocalists, interspersed with a few comic-book characters who really belonged to an earlier stage of my adolescence.

But I still saw Anita around, because Walton was a small place. Too small for her, I thought. I always expected her to leave, because it seemed to me at that time that leaving was the prerequisite for having any kind of a life.

And we were still friends, in the way that people who’ve collected frogspawn and played knock-down-ginger and climbed on factory roofs together will tend to stay friends. I bought her the occasional drink at the Breeze or the Prince Arthur, and we’d share family news. She’d ask how Matt was getting on at the seminary, and I’d lie because I didn’t really know. And I’d pretend to take an interest when she told me about Dick-Breath’s progress at the Prudential, from doorstep insurance salesman to team manager and all-round messiah.

Once - only once - I made a pass. It was New Year’s Eve, when you can get away with a lot of indiscriminate kissing: the general rule being that you took it as far as you could and had a plausible get-out clause if the lady objected. I swung into the Breeze with a couple of mates ten minutes before the towel went up, hog-whimpering drunk, kissed my way down the length of the bar - maidens and matrons and all - until I got to Anita who was standing in the corner watching her cousin feed the one-armed bandit.

We clinched, and it was good. Deep, and intense, and lasting as long as our lungs did. But when I tried to come back for seconds she touched the tips of her fingers, very lightly to my chest, and shook her head. I saw tears rising in her eyes, and I was alarmed. Tears? For who?

‘You okay, ’Nita?’ I asked her, taking pains to get the consonants in the right order because being able to handle your booze was part of the measure of a man in Walton.

‘I’m fine, Fix,’ she said, looking away for a moment while she blinked the tears back under control. ‘I was just - I was waiting for someone, and he didn’t come. I’ll be all right.’ She looked up at me again, giving me a dazzling and almost completely convincing smile.

I bought her a Babycham, which she didn’t touch.

We talked about politics and punk rock - and then, when I was really drunk, I told her about what I was and what I could do with a tin whistle. This was before the rising of the dead went from a trickle to a torrent, and long before exorcism had become an everyday profession, but Anita listened without comment. When I got to the part about my sister Katie, she pressed her hand to the back of mine where it rested on the table, willing me comfort.

I walked her home, and she gave me another kiss. On the cheek, this time: a thank-you kiss. I realised that that was as far as it was ever going to go between us, and I didn’t mind because it was cool that we’d had that moment of contact rather than a grope, a hangover and a lingering sense of embarrassment.

But whoever it was that stood her up that night, he needed his fucking head examined.

I like the Royal London: it’s got a bit of class, as hospitals go. Tell me it wouldn’t lift your spirits to be wheeled out of an ambulance past that terrific eighteenth-century façade. ‘Bloody hell,’ you’d think, ‘I’m going up in the world.’ But the neo-brutalist nightmare they’re nailing onto the back of the building is a different bucket of entrails entirely, and for my money you can keep it.

Kenny was in intensive care, Coldwood had said. I walked in off the street, striding straight ahead past the A&E reception desk and the assembled sick and lame. I was gambling on the ancient truism that people are much less likely to challenge you if you look like you know where you’re going, and it seemed to work: or at least it got me a long way, through A&E and Outpatients and into the slightly dilapidated annexe where the intensive-care wards were located.

The dead watched me every step of the way. In fact, I was having to walk right through some of them, because they were as thick on the ground as leaves in autumn - and like leaves in autumn they presented a rich, mesmerising spectrum of decay. Lots of people die in hospitals, and they

die from a lot of different things, all of which leave their marks on the spirit as well as the flesh.

Nobody knows why some people get up again after they’ve been laid in the grave and others don’t: Juliet puts it down to a character flaw, a fear of taking the necessary jump head-first into another mode of existence. But she’s always fought shy of explaining how that other life works or where it’s situated or how much a square meal costs there.

These ghosts, anyway, were mostly afraid and mostly confused. Their deaths were variations on a theme: arbitrary, painful, early, undeserved, uncomprehended, lingering, undignified, lonely, pointless. They were exactly the type - if you can talk about the psychology of the dead with a straight face - to retain the trace of their injuries and diseases in their risen forms. So I was looking at, and stepping through, a standing exhibition of all the horrible things that can go wrong with the human body both when it’s damaged from outside and when it rises against itself.

Some of them tried to talk to me, their voices thin and high and warped by a distance that wasn’t purely physical. I ignored them and kept on walking. There was nothing I could do for them, apart from playing them the short, sharp tune that would push them off the rim of oblivion - and I don’t do that kind of thing any more unless my back is really to the wall, for the simple reason that I don’t know where I’m sending them. I’m a Pied Piper who learned somewhere down the line to see the rats’ point of view.

Following the signs I climbed a stone staircase enclosing the wrought-iron gridwork of a Victorian elevator, coming out onto a wide landing whose quarry-stone tiles were ancient enough to be dished in the middle.

Unfortunately there were two intensive-care wards, one to each side at the head of the stairs - and each of them was behind a set of double doors that bore a chrome lozenge at chest height on the left-hand side: a digital combination lock, known among professional thieves as a yes-or-no.

The riddle of which ward Kenny had been admitted to was solved immediately by the uniformed constable standing guard on the door to my right. That just left the two obstacles - the lock and the copper. Maybe I could use the one to fend off the other, but only if I got the timing right.

Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water The Steel Seraglio

The Steel Seraglio The Naming of the Beasts

The Naming of the Beasts Dead Men's s Boots fc-3

Dead Men's s Boots fc-3 The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle The Naming of the Beasts fc-5

The Naming of the Beasts fc-5 The House of War and Witness

The House of War and Witness Dead Men's Boots

Dead Men's Boots The City of Silk and Steel

The City of Silk and Steel The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel

The Naming of the Beasts: A Felix Castor Novel The Devil You Know fc-1

The Devil You Know fc-1